Archeological Sites Of Northeastern Illinois

Exploring Ancient Land Use In The I&M Canal National Heritage Area

Hello, everyone, and welcome to another edition of Canal Stories, a series brought to you by the Canal Corridor Association to celebrate the 175th anniversary of the Illinois & Michigan Canal and the communities that were shaped by its legacy. Last week, we dug into the history of archeology in northeastern Illinois and explored the various periods of human occupation in the region. Today, we’ll take an in-depth look at the major archeological sites in the National Heritage Area and examine the stories they tell us about those who walked the land in bygone eras. This is Part 2 of Archeology In Northeastern Illinois, a story brought to us by J.A. Brown from the Department of Anthropology at Northwestern University, which was originally printed in an informational brochure by the Illinois and Michigan Canal National Heritage Area and the National Park Service.

As you explore the hills and valleys of the National Heritage Area, you might wonder where ancient communities took up residence. Well, it just so happens that archeologists have a pretty good idea of the preferred locations. Bluff edges have been favored from the earliest times, although they were rarely lived on for very long or by many people. It is believed that these bluff edge sites were selected in Ice Age times because they offered all-important vistas for sighting herds of roving game animals. Much more important was the high land in valley bottoms, particularly at places along the Illinois River, where the woods made broad belts of habitat for forest dwelling animals. The resources of these forests, together with those of nearby prairies and rivers, provided the most secure sources of food for prehistoric people. Even with the introduction of corn, or maize, native plants and animals continued to have an important place in prehistoric diets.

In prehistoric times, the river was just as important for transportation as it is today, but before the construction of the I&M Canal, the rapids that punctuated the river forced early travelers to walk around them. As one ascends the river, the first of these rapids lies opposite Starved Rock. Although it is buried by the present lock and dam, the obstacle that the rapids presented led to the early development of villages and cemeteries by peoples clustered around this important break in transport.

Large mound groups, now called the Utica Mounds, once occupied both banks near where the Route 178 bridge crosses the Illinois River. The peak of burial mound construction was in the Woodland Period, particularly between 100 BC and AD 100. These mounds contained objects, such as sea shells, that testify to long-distance trade to Florida. Other villages and earthworks were located near portages ascending the river, as well.

Before the I&M Canal, low water during the dry summer months rendered river travel practically impossible. In these and other low-water periods, aboriginal peoples found it easier to strike off on overland trails. The more important of these were taken over by European settlers as the right-of-ways for the early plank roads. These have long since been improved to become our state and federal highways. One of these early routes was the Ottawa Trail, which became the modern day Joliet Road. Camps were set up along the bank, where this trail crossed the Des Plaines, and these trail crossing camps have quite a long history. In fact, the Ottawa Trail Camp has been occupied for 2,000 years.

Starved Rock Area

Starved Rock is probably the single most prominent historic place connected with early Native American life in the area, and this striking pedestal of sandstone has a colorful history to match. Its name comes from a semi-legendary disaster that befell a group of Illinois Indians besieged on its top in the aftermath of Pontiac's Uprising around 1769, but archeological investigations of a large part of the top of the rock have revealed this landmark to have witnessed approximately 5,000 years of continuous human use. All but the PaleoIndian Period is recorded in this long sequence of repeated occupation.

The rock, or as it was called by the French, Le Rocher, became famous in 1682, when LaSalle constructed Fort St. Louis at the top to encourage the Illinois Indians to remain in the village (Old Kaskaskia) after they had been scared off by an Iroquois war party in 1680. The fort's wooden design was tailored to fit the topography and utilized locations where the surface soil was anchored most securely. Several sunken bunkers were dug into areas were the mantle was sufficiently deep. Archeologists excavated a deep deposit of early 18th century trash in one of these bunkers.

When the fort was abandoned in 1691, it remained in use by Native Americans. Deep pockets of trash that filled the bunkers of LaSalle's fort testify to this use, probably by one of the Illinois tribes—perhaps the Peoria—who were recorded to be living near the rock as late as 1736. The rock's present-day name would not come into use until sometime after 1769, while clues to the rock's prehistoric use are buried in the soil that occupies a deep basin-like depression in the rock surface, where ancient campfires were found.

Several hundred feet east and downslope of the Starved Rock Park Lodge lies the Hotel Plaza Site, which was occupied repeatedly in ancient times. This encampment was heavily used in the 17th and early 18th centuries by Native Americans who concentrated around Starved Rock as a defensive measure, and this rich history was revealed by excavations in 1948.

Across from Starved Rock lies the Old Kaskaskia Village, or the Zimmerman Site, which has a 1,000-year old history as a preferred location for farming. This village, much of which lies under the water of the flood pool behind the Starved Rock Lock and Dam, achieved its fame as the site of Father Marquette's visit to the Kaskaskia Indians in 1673. When first found by the French, the village held 74 cabins of long, loaf-shaped wigwams covered with reed mats. The size of the village grew shortly thereafter, by the addition of other groups of Illinois Indians, and reached a size of 460 cabins before the Iroquois raid of 1680.

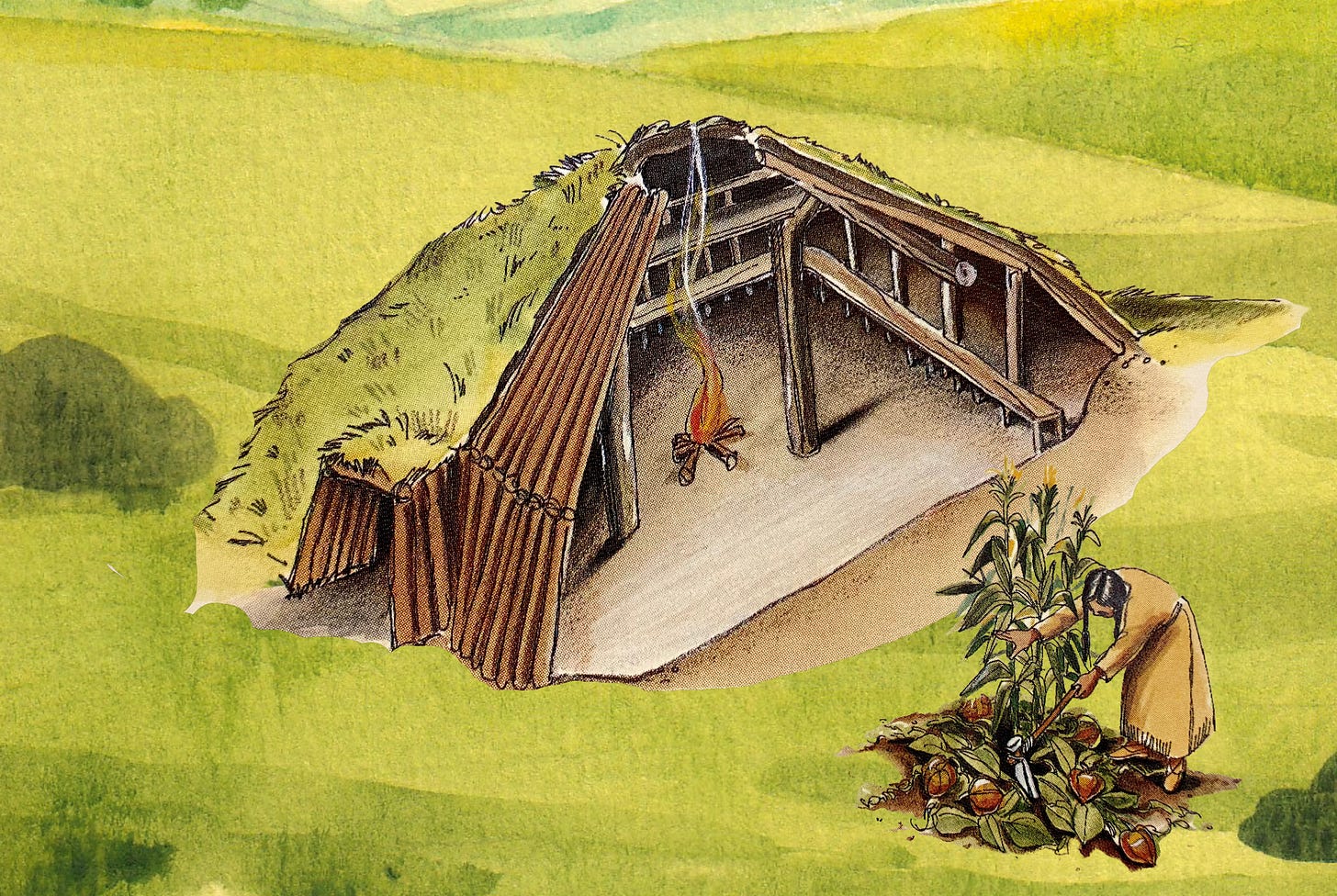

In a beautiful harmony, archeology and history agree upon the lifeways of these villagers. They took up residence in the village during the spring and summer months, and then roamed the upland prairie in search of bison or American buffalo in the early winter and in midsummer, before the corn harvest. Although large game animals were not as plentiful here as they were west of the Mississippi, herds were still an important source of food. Prehistoric occupants of this village lived in very different housing and pursued a more sedentary existence. Dwellings were earth-covered and set part way into the ground, to resemble the earth lodges of the Plains Indians.

Channahon Area

The largest village site in the valley was the Fisher Site, which once stood strategically on the south bank of the Des Plaines River, opposite Dresden Heights (above the I&M Canal State Trail), a few miles upstream from the Des Plaines's convergence with the Kankakee River. This large, 16.5-acre village site originally contained 9 mounds and over 50 earth lodges, marked by saucer-shaped depressions. A large plaza stood at one end, encircled by houses, and along one side stood two large, low burial mounds. Although repeatedly investigated by archeologists since the '20s, most of the site remained unexcavated by the time it was destroyed due to gravel quarrying. Most of the occupation at the site was during the Mississippian Period, although the Woodland Period was represented by one of the mounds.

The best preserved of a now-rare earthwork are the two Briscoe burial mounds. Constructed approximately AD 1100 to 1200, during the Mississippian Period, these mounds occupy a prominent overlook on the north side of the Des Plaines River Valley, just west of the Interstate 55 crossing near Channahon. They are now owned by the State of Illinois.

Joliet Area

The Oakwood Mound is a low, broad burial mound that has been partially excavated, representing the same type of burial place as the lower of the two Briscoe mounds, although Oakwood may be a little older.

The Higginbotham Woods Earthwork is an irregularly-shaped earthen embankment located in a City of Joliet park. It most likely belongs to the Hopewellian Period, when earthworks of similar design were created up and down the Illinois River Valley. Although little has been found at this site by archeologists to date this earthwork, there is no evidence that this is a historic fort, as was once commonly believed. Higginbotham is the last of the ancient earthworks that once lined the Illinois-Des Plaines rivers.

That concludes today’s Canal Story. Thank you so much for joining us as we continue our journey through the history of the Illinois & Michigan Canal. If you’ve enjoyed this episode, pass it along to your family and friends, be sure to leave us a like or a comment, and we’ll see you again very soon.