Canal Diggers, Church Builders - Part 2

Dispelling Stereotypes of the Irish on the Illinois & Michigan Canal Corridor

Author(s): Eileen M. McMahon

Source: Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1998-) , Winter 2018, Vol. 111, No. 4

(Winter 2018), pp. 43-81

Published by: University of Illinois Press on behalf of the Illinois State Historical Society

In June 1839, Bishop Bruté expressed some satisfaction with his growing church in the I&M Corridor. In a letter to Mother Rose in Emmitsburg, he wrote: “Arrived yesterday night from the line of the works of the Illinois canal. . . . I would take more pleasure to speak of the shanties where I have lived, and have done some duty these few days past; but now I am in the city [Chicago], and owe myself as well to the city as to the shanties.”53 Bishop Bruté clearly saw these Irish communities with different eyes that Joseph Buckingham.

The Catholic Church was only able to meet the needs of the harried ranks of the canal diggers by drawing upon its diverse spiritual community in Europe. Shortly before his death, the aged Bishop Bruté personally appealed to Bishop Celestine de la Hailandière of Cambourg, France, for priests. The French bishop sent French cleric, Father Hypolite Du Pontavice, to minister to the Irish canal workers west of Lemont (Figure 3). Father Du Pontavice came from Rennes, France, and soon found himself dispensing the sacraments in a collection of shanties the Irish grandly dubbed “Cork Town” after the Irish city. His task soon became more difficult when, on March 14, 1840, Father Plunkett was killed when riding on the canal towpath. His horse reared and threw him into a tree. Father Du Pontavice became the second resident pastor responsible for the canal mission.54

From Joliet, Father Du Pontavice and fellow priests who came to join him, affectionately called “Holy Tramps,” traversed the canal tow path to serve the work camps along the Summit section of the canal now Lemont and Lockport. Camp Sag was one of the first work sites along the canal route near the present site of St. James’s Church of the Sag. The parish claims it was founded in 1837, but until 1846, parishioners heard mass and received the sacraments in someone’s home only every three to four months when a priest could make the journey from Joliet. From 1846 to the completion of the limestone church in 1852, a log cabin served as a church on Sundays and as a school the rest of the week. In 1852, the present church was begun and completed in 1858. The stone was donated by the owner and operator of a nearby quarry, Peter Roughnot. Local farmers did the masonry work and the carpentry work was done by two Dublin men. Up until 1878, St. James’s was known as Sagganash Church or Sag Church. It was not until the early 1880s that St. James finally had a permanent resident pastor.

Catholicism came to the canal’s Western section thanks to the efforts William Byrne. Byrne was awarded the contract for the portion of the I&M from Peru to Marsailles (Figure 4). Tall and imposing, Byrne emigrated with his family from County Leinster, Ireland, and first settled in Pittsburg. He came to LaSalle in 1837, where he built a log cabin for himself and his family on a bluff near present day Canal and Joliet streets. There, he oversaw the canal project and the scenic Illinois River Valley. His crew built the aqueduct over the Little Vermillion River and the locks to the west. With a reputation as a fair and decent boss, Byrne attracted many of his fellow countrymen, who were eager to work for him.55

By December 1837, Byrne recognized the need for spiritual and institutional discipline of his crew and wrote Bishop Rosati asking for priests. Rosati replied in January 1838, asking what kind of priest would be suited to the mission. Byrne was under no illusions about the men who worked under him and warned Rosati:

The people, a very large majority of them are Catholics; I regret to add, tho. With strong and national attachment to the Catholic religion, yet ignorant of its divine precepts—with this devotion to religion is combined all the ardent feelings and propensities of their early education and country—I speak of the Irish Catholics, as there are few else.56

However, Byrne assured Rosati that he could collect one-thousand dollars “in one or two months from the contractors, superintendents and laborers of the work and those interested in the prosperity of the place.”57 Byrne clearly knew these were rough workers, but unlike the Yankee Protestant elites, he did not see his fellow countrymen simply in that light. Like himself, he saw they want to start a new life.

On March 29, 1838, two Italian Vincentian priests arrived in Peru— the head of navigation on the Illinois River. They were Father John Blaisius Raho, C.M. and Father Aloysius John Mary Parodi, C.M. Father Parodi was born in Genoa, Italy, where he studied for the priesthood. He emigrated to Perry County, Missouri, and was ordained at St. Mary’s Seminary. He was twenty-seven when he came to La Salle. Raho emigrated from the Kingdom of Naples and joined the Vincentian order in Italy and arrived at St. Mary’s Seminary in 1834. He was in his mid-twenties when Rosati assigned the pair to the canal camps where their task was to found a Mission at LaSalle/Peru.58

When they arrived, Rosati and Raho were greeted at the dock in Peru by approximately 500 men, women, and children, Catholic and Protestant alike. The crowd escorted the two priests to Billy Byrne’s cabin by torchlight, as a band played the popular Irish tune “Garry Owen.” The welcome celebration continued until dawn and so impressed Father Raho that he wrote to a superior in Paris, “We had difficulty believing our eyes and shall not again meet with so beautiful a reception; it was for us a happy augury for the success of our ministry in the midst of a people so favorably disposed in our regard.”59

On March 30, Father Raho offered mass in Byrne’s cabin. On April 1, 1838, a throng of the faithful gathered for a Passion Sunday mass at John Haynes’s boardinghouse where doors and windows were thrown open, so all could join in. Father Parodi wrote that “I was moved at the sight before me.” The priests baptized thirty children and heard confession. That year, the Catholic population in LaSalle swelled to 2,000.60

The Catholic community thrived in the Western section and kept Raho and Parodi busy with Sunday masses at Haynes’s boardinghouse and, when weather permitted in a nearby woods. During the work week, Byrne hosted daily masses in his cabin. Beginning with just a modest collection of twelve dollars, the two priests gradually collected enough money for a proper church and rectory. As their community grew, the two priests traveled along the canal route to minister to workers on the line.61 These priests clearly viewed a different Irish community than Buckingham and other outside observers. This positive first impression, however, was severely challenged in the coming months.

The cholera and malaria epidemics that plagued the Summit and Middle sections of the canal raged through the Western section as well. One observer claimed that 1,000 men out of 1,500 died of “over-exertion and the diseases incident to the climate, fever and ague and bilious weather.” Bishop Rosati in St. Louis read reports of 600 to 700 deaths. No doubt the numbers under such conditions were hard to quantify but the experience for all was horrifying. In a letter to his bishop, Father Raho reported that in La Salle, “the diseases in this area are horrible and so many die that there is hardly any time to give Extreme Unction to everybody. We run night and day to assist the sick. For three weeks the temperature was excessive, up to 110F, and this for a few days in a row.”62

In a letter to Father O’Meara in Chicago dated August of 1838, Father Raho wrote, “The season here has been very sickly, and we have been very busy in visiting the sick and burying the dead, and would to God, that His holy justice was appeased.” His bone-tired weariness is apparent as he wrote, “Day and night we both have been laboring, in order to afford the help of our religion to the poor sick. I do not know how long it will last. The will of God be done. Amen. . . . We are tired.”63 Father Raho also made an appeal to Rev. John Timon, the Vincentian provincial supervisor and vicar general of the St. Louis diocese, asking him to, “Pray for us who have no time for anything to give us strength in order to be able to assist all those who are dying . . . and would to God the His holy justice was appeased.” He ended, “The will of God be done. Amen.”64

This dire situation prompted Father Raho to appeal to the Sisters of Charity to nurse the sick men, and set about to raise money to build facilities for them. He described to Rosati his plans, “In winter and spring I’ll save money to prepare a place to cure these people . . . [who] die like dogs among dirt and mud.”65

If battling disease and death were not enough to contend with, in 1837 a depression hit the country after Andrew Jackson’s administration dismantled the Second Bank of the United States. The State Bank of Illinois suspended specie payment, and by 1839 banks collapsed throughout the country. A world-wide recession added to the economic misery. Over the winter of 1837 to 1838 workers’ wages were reduced threatening starvation for their families. The ditch diggers went on a rampage through the canal zone destroying property and equipment. Fearing for his life, one contractor shot one worker dead.66 In another instance, I&M contractor W.M. McDonald was held ransom in a shanty for several days by angry workers whose wages had been reduced. He was rescued by canal trustee Jacob Fry who promised the laborers a deal on their wages. Once in a safe place, however, Fry fired them.67 In June 1838 a group of citizens in LaSalle alarmed by Irish violence petitioned Governor Joseph Duncan to provide weapons from the public arsenal.68

In this horrific setting of disease and destitution, the Irish also took their anguish and frustrations out on each other. When Irish workers joined crews, they generally preferred to work with men from the same region in Ireland. In late eighteenth and early nineteenth century Ireland, secret societies flourished as an outgrowth of poverty and grievances against the exploitative landlord system. Violence originally intended against a hated landlord was sometimes redirected at poor peasants from other counties. These societal associations and animosities carried over to many canal projects in the United States as each group tried to control access to jobs. On the I&M Canal one of the major factions was the “Corkonians” who hailed from County Cork in the south of Ireland. “Fardowners” were northern men from Ulster. They probably were affiliated with the Ribbon Men who in the old country fought Protestant Orange- men. Both groups were predominantly Catholic, but these impoverished, ill-educated men failed to see their common predicament. The priests who came to minister to them were frustrated that these men even refused to attend mass together.69

The first reports of violence among the Irish occurred in early May 1838. By June-July, a full-scale “Irish War” broke out in the Western and Middle sections of the canal. A local newspaper described these conflicts in a colorful and disparaging manner that masked the seriousness of what was taking place:

Representatives from different parts of Ireland gathered into separate settlements, and raising the old songs and war-cries that have so often torn ‘the Harp of Erin’ to tatters, they have reenacted the refreshing dramas of ‘Donny Brook Fair’ and the ‘Kilkenny Cats,’ in which every spring of shillalah was rampant and restless. Funerals and wakes followed on the heels of each other—wakes being productive of more funerals, and the funerals of more wakes!70

On the Western Section, Corkonians attacked Fardowners in Marseilles. Father Raho described for his bishop its causes. “The reason was that the leaders called Corkmen did not want the workers from northern Ireland (that they call Fardowns) to work on the canal.” Raho felt the Corkmen were the instigators. “They want to be the only ones to work on the canal and therefore try to force the Fardowns to give up and leave,” he reported. “They ravage and destroy their cabins and harm them in any way they can.” Fortunately, no one was killed.71

From Marseilles, the Corkonians marched towards Ottawa. There they were joined by a man named Edward Sweeney and a crowd that observers estimated to be between 85 and 200 men. This mob continued westward along the work line attacking any Fardowners they found and destroyed their shanties. Sheriff Alson Woodruff raised a posse and asked Deputy Zimri Lewis from Peru to meet him in Ottawa the next day. They joined with Billy Byrne, a Fardowner, whose men were chased off the line. When triumphant Corkonians reached LaSalle, Ottawa Sheriff William Reddick, a native of Ireland, and Billy Byrne stood their ground and ordered the men to lay down their arms. When they refused, the sheriff and his men fired on their own killing seven.72

This experience shocked and traumatized the two Catholic priests. Father Parodi wrote a harrowing account to the bishop of the riot:

Yesterday afternoon at five about two hundred Irishmen passed through LaSalle armed with guns and sharp sticks. Without any reason they went down to Peru insulting the people of the adverse province. Many were beaten so badly that they were bleeding heavily. At night they camped about a mile away from our house, almost all of them were under the influence of liquor. You can easily imagine how much quiet we enjoyed that night. They were resolved to burn all the houses along the Line that belong to people of the hated province without any reason. The following morning they were chased by almost 1000 citizens headed by Mr. Brunit [Byrne?] with whom I shook hands before the undertaking. At three o’clock in the afternoon I heard that more than forty people were already in jail in Ottawa but it was not possible to capture them all. I assure you that I never heard anything like this: now I know how national passion can carry people to these excesses.73

Father Parodi closed by saying that the Irish “call themselves Catholic and are worse than infidels and care only about money and liquor.”74 What Parodi did not tell his bishop was that he fled to a house three miles away from the rioters. Father Raho, who was away when the disturbance broke out, vented his frustration with his assistant to Bishop Rosati. “His behavior had been criticized by everybody because he could have stopped the riot if he wanted to. . . . Everybody told me: ‘Father, if you had been here everything would have been done and every difference ended.’”75

Having been invited to LaSalle by Byrne, the priests may have taken sides with his Fardowners and had less sympathy for the Corkonians. Father Raho claimed it was safer to be in the city of LaSalle where the people, “are quieter, drink less and come to Church. Unfortunately, the same can’t be said of the people living along the line, two or three miles north of here. They are extremely depraved and untouched by the grace of God.”76 Despite his dedication to his mission, Father Raho, like his contemporaries, succumbed to blaming the Irish for disease and death that ravaged their shanty towns. “It almost seems that the Lord wants to pun- ish the workers of the canal for getting drunk all the time, their riots, their fights and homicides,” he wrote. In a moment of despair, he confided, “I am fatigued, I am tired. Would wish to be among the Indians.”77

Despite his own fears and apprehensions, Father Raho nonetheless threw himself into the task at hand and persuaded Corkonians and Fardowners to celebrate mass together—but it was not easy. He described how he managed this to his bishop: “On this occasion I spoke to them inspired by God. To convince them to come, I had to go and pick them up one by one.”78 His efforts and those of his timid assistant Father Parodi gradually bore fruit. By 1840 the Ottawa Free Trader observed that “The Rev. Mr. Raho and Rev. Mr. Parodi are deserving of great credit for their efficient efforts to better the condition and correct the habits of the laborers in the section of the country.”79

In the Middle Section of the “Irish war” forty Irish men were arrested and thrown into the Joliet jailhouse. The Irish priest Father Plunkett, however, was not intimidated by either of these warring factions. “His greatest efficiency, not to say usefulness,” wrote one contemporary who witnessed the priest in action, “was seen in the handsome and rapid manner in which he could quell a riot . . . no sooner did the ‘byes’ get well engaged at their favorite amusement of each other’s heads, than Father Plunkett, armed with his big black leather horse-whip appeared upon the scene.” The “byes” began calling him Supreme Court Plunkett because no one “ever thought of doing anything except getting away out of the reach of the Reverend’s gad as quickly as possible.”80

In Chicago the Irish reputation for depravity intensified as a Catholic priest blamed the Irish and denounced them with “the malediction of God.” He even blamed the Irish for the diseases they suffered due to their sinfulness.81 Only the Cincinnati-based Catholic Telegraph refused to make a blanket condemnation of all the Irish claiming there were only “a few troublemakers” and credited Irish priests for “pacification” of this group.82

This faction fighting of Irish workers, however, became so worrisome that Bishop Bruté dispatched Father Simon Petit Lalumière, a native-born priest from Vincennes, to the canal corridor. He had specific instructions to investigate the growth of Irish secret societies. Father Lalumière not only investigated the causes of conflict, but played a role in deescalating the situation. Like the other priests, he made “a commanding appeal to their faith,” wrote a contemporary observer, which “made the laborers instantly disperse. He exhorted them to behave as true Irishmen, and true Catholics, worthy of the country of their adoption.”83

Bishop Bruté also visited Joliet that summer. He then reported to New York Bishop John Hughes, a native of Ireland, to intervene in these disputes on behalf of his fellow compatriots. Bishop Hughes wrote to these Irish Catholics threatening excommunication of any one who belonged to such an organization. By 1840, the American Catholic hierarchy condemned these secret societies.84 A universality of a Catholic and Irish identity began to take shape in the I&M Canal Corridor.

Alcohol was a considerable factor in the explosive violence that plagued the canal route during its construction. Canal commissioners were well aware of the problem and tried to control the flow of alcohol through contracts. Initially, contractors had to agree to “not sell or use, or permit to be sold or used, within or near the limits of said job, intoxicating liquors either to persons in their employ, or to any other persons on or near the Canal line.” Canal laborers, however, sought out “wet” contractors who ignored these regulations. When violators were found out, however, they lost their contracts, but it was impossible to stop people from drinking no matter where they got it.85

Buckingham, however, described how difficult it was to control the flow of alcohol:

At first the [canal] Board made it a stipulation that no person employed by them should use spirits; but they could get no man on this condition. They next allowed them liberty to use it, if purchased by them- selves, but abstained from supplying any from the general provision store. Even this, however, they were at length obliged to abandon, in order to keep their men, they majority stipulated they should have a certain number of gills of whiskey or rum per day, served at the expense of the canal fund, in addition to their dollar a day and log huts rent free.86

Alcohol abuse, however, was not an Irish import. This attempt at social control flew in the face of the common practice in antebellum America that linked hard labor with the use of hard liquor. Historian William Rorabaugh dubbed early nineteenth century America as “The Alcoholic Republic” because of the widespread consumption of spirits. He documents that across the country, from rural harvest hands to urban carpenters, workers expected to have whisky with their mid-day meal. On many canal projects, whisky was doled out by contractors as part of the diet. Others gave workers whisky in lieu of or as a supplement of their pay. Frequently, contractors used whisky as an incentive to work longer hours or to reach certain construction goals. Whisky could also be a genuine source of profit for a contractor. Monthly pay doled out to workers laboring on isolated sections of the canal could quickly flow back into the contractor’s hands if he operated a saloon tent.87

The common Irish canal digger faced formidable obstacles to staying sober and subsequently peaceable in these circumstances. Once again Catholic priests played a key role in nurturing a different behavior. Canal contractor Nathaniel Brown was not a Catholic, but he had heard about Father Mathew’s Temperance Union. Father Theobald Mathew was an Irish Capuchin priest who established the Cork Total Abstinence Society in the spring of 1838. To join, one simply promised to refrain from alcohol. By the end of that year the movement spread throughout Ireland where estimated 150,000 people took “The Pledge.”88 Brown approached the priests in the canal corridor to establish a local chapter to help quell violence and disorder. Some canal workers thought the movement had little chance of success as they argued only a drunken man would do the work.

However, thanks to the diligence of Catholic priests, alcohol consumption did decline. Father Du Pontavice turned many Irish laborers into “cold water men”—or temperance men. As an example, he and Father Gueguen gave up the “vin rouge” or red wine favored by the French.89 Presbyterian minister Jeremiah Porter, a missionary of the American Home Society, observed that priests “were exerting themselves with effect in this cause [of temperance]—within a few weeks they have administered the pledge of total abstinence from all that can intoxicate to several hundred persons on the line.”90 In 1841 many Irish celebrated St. Patrick’s Day without drinking and mayhem. The Ottawa Free Trader attributed it to the new temperance association. The paper reported, “The pledge to abstain from intoxicating liquors has been taken in the most solemn manner by a great portion of the Irish community on the line of the canal.”91 The lack of public drunkenness by 1841 was also probably due to fewer single men on the work site who left when funding collapsed.

By 1840, the State of Illinois and canal commissioners realized they needed to reorganize the project. To keep workers on the job, the State and the commissioners paid workers in scrip, which was essentially an IOU. Married men, desperate to feed their families, exchanged their scrip for food and other basic necessities at the Lockport stone warehouse. Warehouse managers, however, had been free to set prices on goods as long as they enjoyed a monopoly and could extort a man out of his hard-earned wages. Since this practice might drive workers off the job, the commissioners then had to closely monitor warehouse prices. It was not until towns developed and local businesses broke the warehouse’s monopoly, however, that workers could exchange their scrip at market rates for goods.92

Some Irish workers used scrip to buy land along the route and turned to farming. August Dolan, a native of Ireland is example of mud-digger turned farmer. He arrived in Lemont in 1837 and worked on the canal until 1840 when worked stopped. He then started raising stock, and by 1845 he was able to purchase a 160-acre farm near Sag Bridge during a canal land sale. Dolan also served as Lemont’s first town assessor and commissioner, and for twenty-four years he served as school director. He also served a three year term as trustee of school property.93

Thus, the Irish began their transition from temporary workers to permanent settlers along the I&M Canal Corridor and Catholic priests worked to build permanent houses of worship. Raho and Parodi asked the canal commissioners to donate land for a church in LaSalle. The canal company, no doubt interested in stability in the Irish community, offered land near Third Street and Chartres. Construction began in June 1838 and was completed within a month. Canal laborers along with local farmers built the modest structure on Sundays when they were “off” work. With the help of draft animals borrowed from canal contractors, Irish men cleared the land and dug drainage ditches. They hauled, sawed, and pegged into place the fifty feet by twenty-five feet log church. It was originally called the Church of the Holy Cross, complete with a steeple with a cross fitted with a bell purchased in St. Louis. Parishioners claimed it was the first church bell heard between St. Louis and Chicago when it rang on August 4, 1838.94

By Christmas, parishioners had much to mourn but also accomplishments to be celebrated. By the end of 1838 the Church of the Holy Cross had approximately 1,000 parishioners with ninety-five baptisms, seven marriages, and eighty-five funerals—most from deaths due to the cholera epidemic.95 Father Raho recounted the joyous excitement of the parish as he celebrated midnight mass, the 5:00 a.m. mass, and an 11:00 a.m. mass in which even local Protestants joined their Catholic neighbors. At all the masses the church was filled. Raho wrote that at the midnight mass, “especially at the time of the elevation of the Host, and Chalice a unanimous sigh of joy missed with tears was heard. . . . Thanks to God, in 9 months this people has reformed entirely their evil way. I hope they will persevere.”96

Raho’s satisfaction was still evident in January 1839, when he wrote to Rev. John Timon, the Vincentian provincial supervisor and vicar general of the St. Louis diocese of his affection for his charges in LaSalle: “. . . In this Congregation the feast of Christmas was celebrated with great edification, and advantage to the soul. . . . For the Feast, the Church was, though poor, but decently, and neatly decorated.”97

The La Salle Mission continued to struggle, however, through the years of economic downturn. An estimated 80 percent of La Salle residents left their homes with 10 percent going into farming in the hinterland and others moved west. Poverty plagued those who stayed until funding for canal work resumed in 1845.98

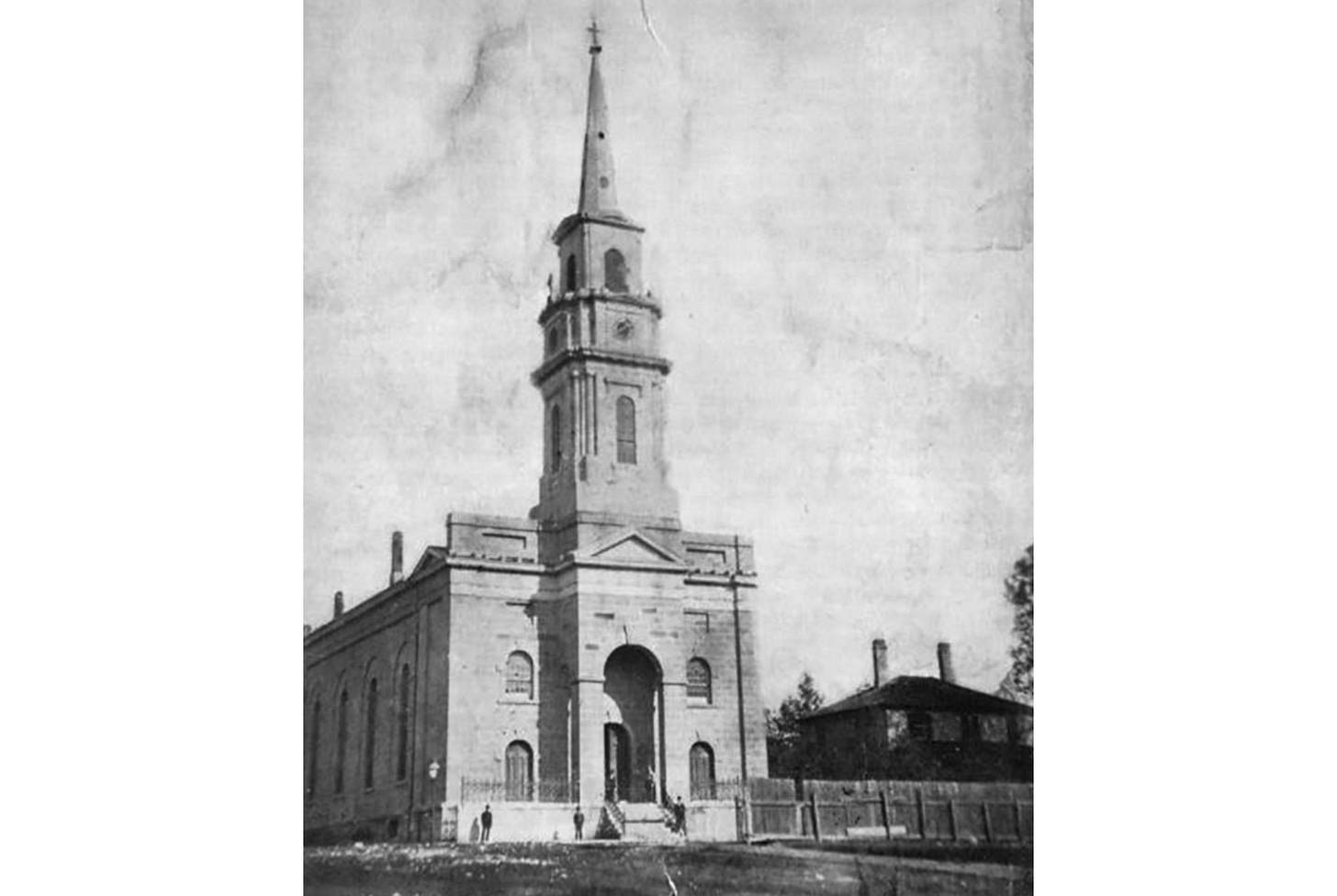

By May 1846, Father Raho was reassigned and left the La Salle Mission to serve as vicar-general of the Diocese of Monterey. Father Parodi also found a new assignment. The two men left behind a well-established parish. Within a decade it had outgrown the log church and canal workers and their families helped the new pastor Father Mark Anthony raise money for a new church. They even received donations from the Catholic cities of St. Louis and New Orleans. Canal laborer Patrick Joseph Mullaney designed a neo-classical building with Joliet limestone, and on May 24, 1846 the building began with a ceremonial blessing. Canal workers put down their picks and shovels and were joined by their bosses as they gathered with townspeople and local farmers for the event. After the blessing, Irish whiskey was passed around and the canal workers commenced digging the new church’s foundation. The church took five years to build as the canal workers were only able to work on Sundays—their day off. Their dedication bore fruition when the new church was dedicated on June 1, 1851 and christened St. Patrick’s Church (Figure 5). By 1855 St. Patrick’s expanded its mission and opened St. Vincent Asylum, a school staffed by Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent DePaul. They taught and cared for day students, boarders, and orphans.99

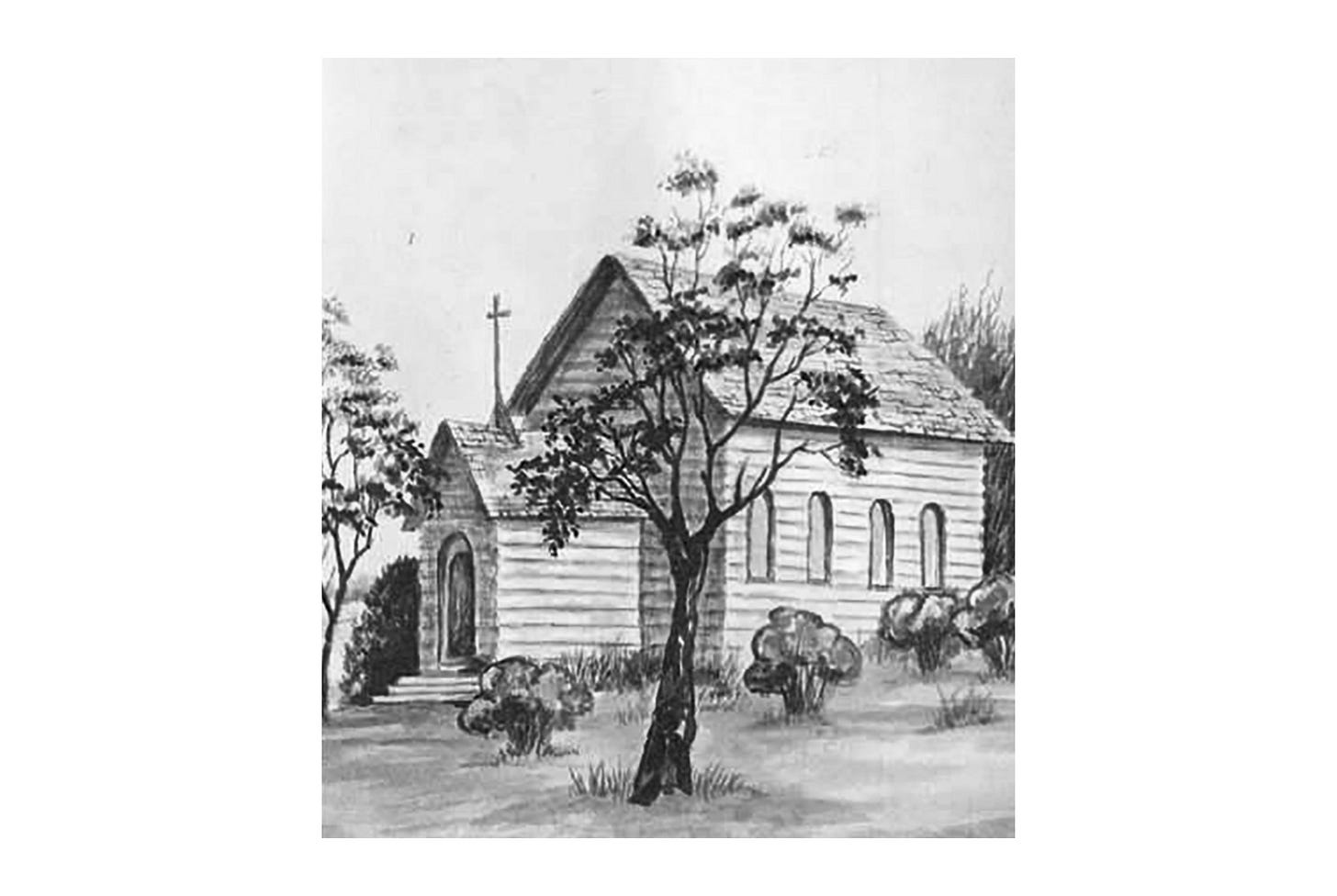

The priests and Catholics in the Middle Section of the work zone also moved forward with church-building during the dark days when funding evaporated and violence and disease plagued their communities. Between 1839 and 1842, workers in Haytown picked up their picks and shovels and drifted to what was then called Emmetsburg on the north bend on the eastern bluff of the Des Plaines River. There, many took up the plow to farm. They brought with them the small wooden church Father Plunkett had built to say mass for them on his visits (Figure 6). Father Du Pontavice continued to serve the Lockport Mission until 1846 when Father Dennis Ryan arrived (Figure 7). Father Ryan was born in County Kilkenny, Ireland, and emigrated to New England in 1814. There he met the Bishop of Boston, John Cheverus, who sponsored his study of the priesthood. For the next few decades Ryan ministered in Maine. When members of his family decided to move to the Illinois prairie and settle in Lockport, Ryan asked for a transfer. There, he worked on his brother’s farm and assisted new settlers. They in turn encouraged him to stay on as their resident priest. Father Ryan agreed and laid the foundation for St. Dennis’s Parish—named in his honor. Sadly, Father Ryan died of cholera in 1852. He was succeeded by Father Michael O’Donnell who initiated the first St. Patrick’s Day celebration in 1853. Sadly, he too died of cholera in 1854, at the age of thirty-six. The present church was completed in 1879 (Figure 8).

Between 1844 and 1848, many Irish, along with some German immigrants, moved on to the next stretch of the canal between Channahon and Seneca. Itinerate priests, such as Father Du Pontavice, traveled on horse-back between the Joliet Mission and Ottawa to minister to workers and their families. The priests celebrated mass in private homes, in the court house, and by 1845, in a rustic building near the canal. It was said to be the first Catholic church in Grundy County. Father Thomas O’Donnell followed Father De Pontavice in ministering to Catholics in the area. Both men eventually died of cholera. Immaculate Conception Parish grew out of this humble community and owes its first permanent church to an enterprising Irishman named John McNellis. McNellis operated a local saloon and boardinghouse that catered to canal workers. He then bought sixty acres of canal land in Morris to farm. He donated a portion of his land in Morris to Father Patrick Terry for a permanent church. Catholicism became a permanent feature of the town as many Irish stayed on as farmers or worked in agricultural related industries. In 1852 that church was completed and replaced by a larger structure by 1867.100

McNellis made an even more indelible mark in Morris when he donated ten acres of his land on the east end of town to Notre Dame University in South Bend, Indiana, founded in 1844, on condition it maintain a Catholic school in Morris in perpetuity. His daughter had attended St. Mary’s of Notre Dame where she became attached to Mother Superior Angela. In 1858 St. Angela’s Academy opened for girls staffed by the Holy Cross Sisters of St. Mary’s. A year later a boys’ school was added. They operated as both a day and a boarding school.101

The next town along the canal route where Irish immigrants sunk Catholic roots was Seneca. Itinerant priests from Morris celebrated mass in the homes of Catholic settlers. Once canal work was finished, many Irish stayed and worked in nearby coal mines or became farmers and townspeople. In 1856, the first church of St. Patrick’s Church was built on the north bluff a half mile east of the present church. In 1868, Father James O’Leary became the parish’s first resident priest.102

Initially, Ottawa Catholics were ministered to by the Vincentian priests from the La Salle Mission. Father John B. Raho celebrated the first Sunday mass in 1838 in a county courthouse through the courtesy of Sherriff William Reddick. Reddick had emigrated from Ireland in 1816, and by 1835, settled in the Ottawa area and went into politics.103 The priests then purchased a carpenter’s shop for a permanent building to service the nearly 500 parishioners. By 1841, the parish built a wood-frame church on West Jefferson Street designed by Ottawa resident Michael Ryan. In 1844, Father Thomas O’Donnell, the first resident priest, began work on a the present church of St. Columba’s. It was completed in 1851 but destroyed by fire later that year. While a new church was under construction, Irish Catholics heard mass in the town’s new Greek-rival-baroque style courthouse demonstrating that Irish Catholics were already politically active in local politics (Figure 9).104

The use of the county courthouse for a Catholic service no doubt would have raised howls of objections in the East. However, that animosity was not present along the Canal Corridor. In this frontier setting Catholics were too numerous, and Protestants welcomed any civilizing institutions.105 Fathers Timon and Parodi even expressed hopes of converting Protestants:“There is no doubt it will be a vast field where our efficacy will have to display their zeal in sanctifying the Catholics, and converting, by God’s grace, the Protestants, who have not many prejudices against us; and many of them would assist at our ceremony.”106

By 1844, Catholicism’s firm foundation in the region led the Church to designate Chicago a diocese and appoint Rt. Rev. William Quarter its bishop. His jurisdiction included the canal communities. While the city still only had one Catholic Church the year Quarter was appointed, that population was growing rapidly. By 1846, St. Patrick’s was established to serve the Irish on the West Side of the city. The Church purchased land from canal commissioners for three-thousand dollars.107 The parish served as a mission for Irish workers on the eastern end of the canal route southwest of Chicago in what was called Hardscrabble because of the poverty of its residents. In the 1840s, a low bridge was built across the Chicago River forcing barges to unload in Bridgeport. When the canal was completed in 1848, the Midwest prairie’s bounty unloaded here in exchange for manufactured goods from the East and lumber from the Great Lakes north woods. Bridgeport boomed with slaughterhouses, packinghouses, brickyards, breweries employing thousands of immigrants. By 1847, the Irish population in Bridgeport grew large enough to support its own parish and St. Bridge’s took shape. Mass was celebrated in the homes of parishioners until 1850 when James McKenna donated Scanlon House to be used as a church. After many delays a brick church was dedicated in 1862 at Archer Avenue and Arch Street (Figure 10).108

Completing the canal project itself, however, continued to be beset with problems to the very end as management and labor fought until the bitter end. An 1847 strike by workers in the Summit division (the area nearest the warehouse) reveals the conflict over class interests that was always just under the surface of the I&M project. In 1845, administration of the project had been restructured as it emerged out of the years of bankruptcy. The canal commissioners were replaced by three canal trustees. Two of these directors were appointed by the creditors of the bankrupt canal and one trustee was appointed to represent the interests of the State of Illinois. Engineer William Gooding continued his daily supervision of the work. For two years following the restructuring progress was sporadic at best. Neither the canal trustees nor contractors were diligent in paying their bills. Workers suffered from intermittent work, long delays in payment, and health problems caused by seasonal malaria outbreaks. In 1844 a virulent strain broke out along the canal from Joliet to Peru. One doctor in Ottawa reported that “the Irish laborers on the Canal had suffered greatly.”109 An outbreak of malaria occurred in October 1846. It was so severe that the canal secretary Robert Stuart wrote to Thomas Ward that “more than three quarters of the officers and men on the line have been prostrated . . . [by sickness] altho’ there have not been many deaths.”110 In an effort to reverse this trend in 1847, the canal trustees elected to do away with contractors and directly supervise work on the Summit division themselves.

In a final push to finish the canal, Gooding worked his construction crews very hard to make up for lost time. The work day often began at 4:00 a.m. and continued until dusk. In July, disgruntled workers, aware of the trustee’s sense of urgency, organized a strike. After walking off the job, they sent an appeal to Charles Oakley, the state trustee. They complained that since “the said work has been worked by State Supervisors, there has been abuse of the Labour and lives of men on said works.” They demanded an increase in wages and a restructuring of the work day to allow the men more time to eat their meals and break up the long day of arduous labor. Their day began 4:30 a.m. and did not end until 7:45 p.m. For this they were paid one dollar. They demanded a fourteen-hour day starting at 6:00 a.m. and ending at 7:00 p.m. for $1.25. Tellingly they demanded to be treated as “white Citizens” and not as “Common Slave Negroes.” Predictably the trustees representing investors in the canal refused to con- sider any raise in pay and Gooding rejected the very idea of bargaining with organized workers. In his view “the principle being once conceded that a combination amongst the men to obtain what the employer is not required in justice to grant, and yields upon compulsion, induces other unreasonable exactions, and finally takes from him all power of control.” In a confrontation that was becoming typical in antebellum America, Gooding articulated the modern argument that labor organization could not be allowed to set the conditions of labor. These conditions must be set by the market and management alone. In fighting this strike Gooding had the advantage of controlling the flow of wages and supplies to the men on the line and their access to food. After several weeks of stalemate the laborers went back to work or in disgust quit the canal for farm labor jobs that offered a dollar a day as well as board.111

In 1848, the ninety-seven mile long Illinois & Michigan Canal, complete with fifteen locks with two summit level locks at Chicago, was completed and many Irish settled into their new lives on the Illinois prairie. U.S. Agricultural census data for 1850 and 1860 for Will and LaSalle counties make clear that many Irish successfully transitioned into farming and small-town occupations.112 Opportunities were available for those lucky enough to survive the ordeal. The ministry and care of Catholic priests played an important role in that transformation, giving workers the hope to endure the backbreaking labor and the despair that accompanied disease and the death of many of their comrades. While they labored on the canal, Irish workers married, baptized and educated their children, and buried their dead in the churches they themselves built. All the parishes founded by Irish canal workers still exist today nearly 100 years after the last barge made its way through Illinois & Michigan Canal.

Notes

53. Garraghan, S.J., Catholic Church in Chicago,103–4.

54. Werling, First Catholic Church, 47–48.

55. Elizabeth Cummings, “The Stone Church: The Story of St. Patrick’s of La Salle, Illinois, 1838–1988,” 8–9, in Local History Collection, Peru Public Library, Peru, IL; Baldwin, History of LaSalle County, Illinois. 380–81. Note spelling of Byrne or Burns in sources.

56. Cummings, “The Stone Church;” Tobin, “The Lowly Muscular Digger,” 167.

57. Tobin, “The Lowly Muscular Digger,” 158–59.

58. Cummings, “The Stone Church,” 10–11.

59. Ibid., 10.

60. Ibid., 11–12; Mark Wyman, Immigrants in the Valley: Irish, Germans, and Americans in the Upper Mississippi Country, 1830–1860 (Chicago: Nelson Hall, 1984), 80–81.

61. Cummings, “The Stone Church,” 12; St. Patrick’s Church Tenth Anniver- sary Dedication, 1899–1909, Reddick Library, Ottawa, IL.

62. Tobin, “The Lowly Muscular Digger,” 129.

63. Ibid., 130–31.

64. Letter from Raho to Rev. John Timon, C.M., August 1838, Rev. John Timon Letters, UNDA.

65. Tobin, “The Lowly Muscular Digger,” 129–30.

66. Andreas, History of Chicago, 384.

67. Tobin, “The Lowly Muscular Digger,” 181.

68. Copy of letter by Thornton and Fry to Gov. Josh Duncan, June 18, 1838, Canal Letterbooks, Illinois State Archives, Springfield.

69. Werling, First Catholic Church, 38.

70. Woodruff, History of Will County, 429.

71. Tobin, “The Lowly Muscular Digger,” 171–72.

72. Cummings, “The Stone Church,” 16; Elmer Baldwin, History of LaSalle County, Illinois (Chicago: Rand, McNally & Co., 1887), 199–200. 73. Tobin, “The Lowly Muscular Digger,” 185.

74. Ibid., 185.

75. Ibid., 160–61.

76. Ibid., 120–21. Here Tobin gets it from Raho to Rosati, August 23, 1838, Rosati Correspondence, St. Louis Archives, St. Louis (on microfilm at UNDA). Original in Italian.

77. Tobin, “The Lowly Muscular Digger,” 129–30.

78. Ibid., 172.

79. Ottawa Free Trader, 2 July 1841.

80. James H. Ferriss, Historical Edition of the Joliet News (Joliet, IL: Will

County Historical Society, 1984).

81. Tobin, “The Lowly Muscular Digger,” 130–31.

82. The Catholic Telegraph, VII, 3 May 1838, p. 162.

83. Werling, First Catholic Church, 38.

84. Werling, First Catholic Church, 38–39; Tobin, “The Lowly Muscular Digger,” 176.

85. Tobin, “The Lowly Muscular Digger,” 95–99.

86. Buckingham, The Eastern and Western States, 229.

87. Articles of Agreement Dated March 30, 1846 between Ben[orn] C. Waterman and David Lotz and Board of Trustees of the Illinois and Michigan Canal for Construction of Lock Gates for Summit Lock No. 1, I & M Canal Documents and correspondence, 1832–1857, Lewis University, Chicago; William Rorabaugh, The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979), 8–11; Way, Common Labor, 181–87.

88. “Theobald Mathew,” Catholic Encyclopedia (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1913).

89. Bankruff and Drake, History of St. Dennis Church, 3.

90. Tobin, “The Lowly Muscular Digger,” 151–52.

91. The Ottawa Free Trader, 26 March 1841.

92. Lamb, “The ‘Drunken, Dirty’ Irish Build the Canal,” and “The Great Canal Scrip Fraud,” 47; Tobin, “The Lowly Muscular Digger,” 138–41; List of Suppliers to Workers, I&M Canal Records, Illinois State Historical Society, Springfield.

93. Andreas, History of Chicago, 852.

94. Cummings, “The Stone Church,” 12–16; St. Patrick’s Church Tenth Anni- versary Dedication, 1899–1909, Reddick Library, Ottawa, IL.

95. Cummings, “The Stone Church,” 19.

96. Rev. Raho to Rev. John Timon, C.M., January 4, 1839, Rev. John Timon Letters, UNDA.

97. Ibid.

98. Cummings, “The Stone Church,” 19.

99. St. Patrick’s Church Tenth Anniversary Dedication, 1899–1909, Reddick Public Library, Ottawa, IL.

100. Lawrence James Lenki, “Immaculate Conception Parish,” in Parishes on the Prairie: Roman Catholic Churches Along the Illinois and Michigan Canal, ed. Eileen M. McMahon (Romeoville, IL: Lewis University, 2007), 81–84. Immaculate Conception Church, Morris, Illinois, Morris Churches File, Morris Public Library, Morris, IL.

101. Lenki, “Immaculate Conception Parish,” 84–85.

102. Seneca Area Centennial Celebration: The Story of 100 Years (Seneca, IL: Seneca-Marseilles World + World Print Co., 1965); Stacy Georginis, “St. Patrick’s Parish, Seneca,” in McMahon, Parishes on the Prairie, 89–93.

103. “History of Reddick Public Library,” http://www.reddicklibrary.org/con- tent/history-0, Accessed 8 July 2014.

104. Eileen M. McMahon, “Illinois,” in The Encyclopedia of the Irish in America, ed. Michael Glazer (South Bend, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1999) and Eileen M. McMahon, “The Rural Irish in Illinois,” Paper given at the Midwest Regional Meeting of the American Conference for Irish Studies at the University of Missouri—Kansas City, October 2007; St. Columba Church Centennial Cele- bration, June 13, 1982, Reddick Library, Ottawa, IL; Jim Ridings, “Greetings from Ottawa—A Picture Postcard Look at Old Ottawa,” Reddick Library, Ottawa, IL, 41.

105. Werling, First Catholic Church, 44.

106. Rev. Parodi to Rev. Timon, February 25, 1841, Rev. John Timon Letters, UNDA.

107. Andreas, History of Chicago, 291, 294–95.

108. Rev. Msgr. Harry C. Koenig, S.T.D., A History of the Parishes of the Arch- diocese of Chicago (Chicago: The Archdiocese of Chicago, 1980), 145–66.

109. Tobin, “The Lowly Muscular Digger,” 131.

110. Ibid., 131–32.

111. Way, Common Labor, 54–56.

112. U.S. Agricultural Census, 1850 and 1860 for Will and LaSalle County.