Canal Diggers, Church Builders - Part 1

Dispelling Stereotypes of the Irish on the Illinois & Michigan Canal Corridor

Author(s): Eileen M. McMahon

Source: Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1998-) , Winter 2018, Vol. 111, No. 4 (Winter 2018), pp. 43-81

Published by: University of Illinois Press on behalf of the Illinois State Historical Society

Spires of Roman Catholic churches tower above the towns and bluffs that line the Illinois & Michigan Canal Heritage Corridor. They are a visible reminder of the aspirations of ordinary people who dreamed of a better life on the Illinois prairie. These houses of worship formed the foundation for permanent Catholic immigrant communities in this region. Many of these churches were founded by Irish canal diggers and their families. They are a testament to their intent to sink roots into the rich Illinois prairie.

These early nineteenth century immigrant Irish canal workers did not leave behind written records of their thoughts or experiences. What we know about their lives is what others at the time said about them. They did menial labor, lived in squalor, drank, and at times, brawled and rioted. In 1840, a British traveler writer, Joseph S. Buckingham, who visited the I&M work site, established this image from a scene he encountered of an Irish camp near Utica:

We had scarcely got beyond the edge of town . . . and a more repulsive scene we had not for a long time beheld. The number of persons congregated here were about 200, including men, women, and children, and these were crowded together in 14 or 15 log huts, temporarily erected for their shelter . . . I never saw anything approaching the scene before us, in dirtiness and disorder . . . whiskey and tobacco seemed the chief delights of the men; and of the women and children, no language could give an adequate idea of their filthy condition, in garments and person; though it required only a little industry to preserve both in a state of cleanliness, for water was abundant . . . and soap is cheaper in this country . . . It is not to wonder at, that the Americans conceive a very low estimate of the Irish people… the large majority are not only merely ignorant and poor . . . but they are drunken, dirty, indolent and riotous, so as the objects of dislike and fear to all in whose neighborhood they congregate in large numbers.1

When they finished the canal, popular lore assumed the Irish moved on to railway work or found unskilled work in growing industrial cities like Chicago.

Historians perpetuated these assumptions because the dramatic historical stage of Irish America was in the rough-and-tumble world of urban politics, labor organization, or on the battlefield. Few scholars have focused on the rural or small town experience of the Irish. They assumed the Irish avoided the vast Midwest prairie because they were just “pick and hoe” farmers, due to the exploitative landlord system in Ireland. The American frontier was also thought to be too lonely a place for the gregarious Irish.2 The Irish, however, were an important presence in rural and small-town America, and the Illinois & Michigan Canal played an important role in introducing the Irish to the farmlands of the great interior of the continent. Dennis Clark, in his work, Hibernia America: The Irish and Regional Cultures (1986) recognized the role of canal and railroad projects in dispersing the Irish to the Midwest prairie and notes a few rural communities with Irish names. Catherine Tobin’s work, “The Lowly Muscular Digger: Irish Canal Workers in Nineteenth Century America,” describes vividly the experience of the Irish who built the nation’s canal infrastructure and the importance of Catholic priests who ministered to them in miserable conditions. Ryan Dearinger’s The Filth of Progress: Immigrants, Americans, and the Building of Canals and Railroads in the West (2016) explores how these infrastructure projects became contested spaces between elite American modernizers and immigrant workers, who he depicts with sympathy.3

How the Irish shaped their own destiny and settled into new towns and cities along the Illinois & Michigan Canal is the focus of this study. They were a more diverse group than commonly thought. Patrick Fitzpatrick is a notable example. In 1833, this native of Ireland came to Chicago, and in anticipation of canal construction, headed out to Lockport, bought 160 acres of undeveloped land, built a log cabin, and became a successful farmer.4 Fitzpatrick gave John Daly, also an Irish native, a start as a farm laborer when he arrived in the canal corridor. Daly did stints on the canal and other menial jobs. He saved enough money to purchase his own farmland, eventually owning a spread of five hundred acres.5 U.S. Census figures confirm their presence in rural areas. In 1850, two years after the completion of the I&M Canal, twenty-eight thousand Irish were living in Illinois. One-third worked in agriculture. Over the next twenty years, the Irish population continued to increase in rural communities in the state and within the I&M corridor where jobs and land were plentiful.6

Buckingham was correct in his observations that the Irish canal community exhibited dysfunctional behavior. However, what he did not see was their desire and struggle to lift themselves out of the squalor, disease and death, and despair of unemployment through appeals to Catholic priests and the stabilizing influence of the Church. The American Catholic Church was poised to begin its mission work in the American heartland as the construction of the canal promised settlement of northern Illinois. Throughout the United States, Irish immigrants utilized the Catholic Church to assimilate into American life as it provided a spiritual and psychological haven in a hostile Protestant society. Catholic parishes were important components to community generation in an unfamiliar and hostile country.7 This is an important part of heritage in the Illinois & Michigan Canal Corridor. This legacy of Irish church-building along transportation routes, however, is not unique to the I&M. Historian Carl Wittke observed, “In New England, as in the West, the rise of Roman Catholic Parishes can easily be traced by following a map for internal improvements projects. . . .”8 Besides the canal, their churches are the more fitting memorial of Irish canal workers than negative stereotypes.

When this region was secured after the American Revolution and especially the War of 1812, Americans began their move to the Great Lakes and Upper Mississippi Valley. Getting there, and more importantly, getting goods back to Eastern markets was prohibitively expensive. The Appalachian Mountains were an obstacle and the rivers beyond flowed west and south. There was no return trip east by water. To tap the vast resources of the interior of the continent, the country needed a modern transportation system of roads, canals, and harbors. The Erie Canal, built from 1817 to 1825, was the first major water highway that connected the Great Lakes territory to the East Coast. The last great canal built in this era was the Illinois & Michigan, which cut through the Chicago Portage to connect the Great Lakes to the Illinois River and Mississippi Valley. These canals made it possible to ship goods to either the Port of New York or New Orleans.

In 1833, in anticipation of construction of the I&M Canal, the State of Illinois incorporated Chicago. New England and New York entrepreneurs began arriving on this swampy terrain in search of their fortune. In 1836 when the canal projects began, these men became the entrenched elites of this promise of a city. The canal commissioners and engineers reflected this social background. They were William F. Thornton, Gurdon S. Hubbard, and William B. Archer.9 The chief engineer and day- to-day overseer was William Gooding. In 1845 three trustees—David Leavitt, William Swift, and Jacob Fry (later Charles Oakley) oversaw the completion of the project. To organize and manage the undertaking, the worksite was split into three major divisions—the Summit (Chicago to Lockport), the Middle (Lockport to Seneca), and the Western (Seneca to LaSalle). These divisions were further divided into sections. Each section extended a quarter to a half-mile in length overseen by a contractor. The contractors represented a much more diverse group of men. Some were major capitalists such as William B. Ogden, Chicago’s first mayor, real estate investor, and railroad entrepreneur, and George W. Dole, a founder of the Chicago Board of Trade and an early player in the grain trade. Many contractors, though, were Irish immigrants who worked their way up from the mass of navigators or “navies” on other canal projects. Their responsibilities were to hire, manage, and dole out the wages to the rank and file laborers. Workers normally had little contact with the canal com- missioners or even the chief engineer.10

The saying “to build a canal you needed a shovel, a pick, a wheelbarrow, and an Irishman” reflected historic forces of the nineteenth century.11 Irish immigration began just as the great American transportation revolution of the nineteenth century demanded cheap labor. In 1818, three-thousand Irishmen were at work on the Erie Canal. Within eight years, five-thousand Irish workers manned four other canal projects where they had earned a reputation for good work. Pennsylvania canal contractor, David Weber, claimed one Irishman could outwork “three raw Hollanders [Germans].”12

However, class, religious, and ethnic tension between management and labor plagued many of these canal projects. The I&M project was no exception. Before work even began, conflict erupted between Chicago’s emerging elite and Irish immigrants. In 1836 notable members of Chicago’s influential class decided to celebrate their up-and-coming city along with the nation’s birth on the Fourth of July. They traveled up the Chicago River to the proposed canal terminus near present-day Bridgeport. They read the Declaration of Independence, congratulated themselves for being a part of this auspicious occasion, and made their way back on the steamboat Chicago. When they arrived back in town, Irish “roughs,” as the local newspaper called them, threw rocks at the steamer. The young men on the boat retaliated and beat the “heroes of the Emerald Isle.” This was not a good omen for good labor-management relations on the canal project.13

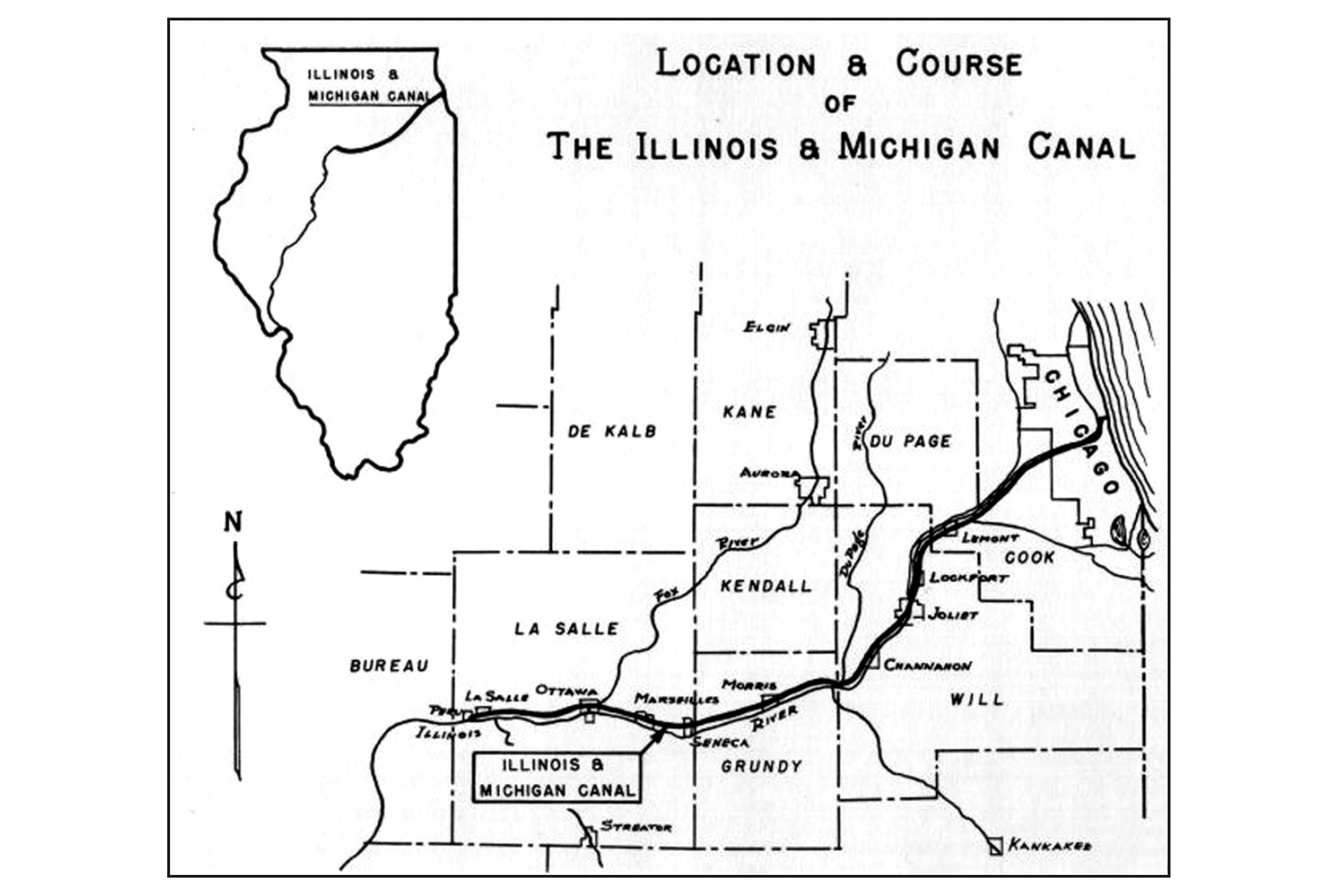

As work got underway, shanty towns sprang up along the canal route and the banks of the Des Plaines River from Chicago to Peru (Figure 1). Everyone expected to make money on this enterprise. One contemporary observer enthusiastically reported that, “the men were all paid at the rate of a dollar a day for their labor, had houses rent free, and provisions of every kind abundantly cheap.”14 From such an upbeat description, one would expect a well-outfitted operation that provided workers with all their needs. However, this was frontier Illinois where supplies of all kinds were hard to get and expensive. Housing was temporary and not always supplied by the canal project as the casual onlooker supposed. The Chicago Daily Journal described the actual conditions of the Irish work camps as being comprised of “all sizes, shapes and materials, sod and straw; shingled or boarded sheds being in great demand. Some of these habitations, if they can be dignified with the title, are wretched looking tenements.” Some “honest Irish laborers” built cabins out of locally harvested timber while “Irish mud-diggers” lived in log huts and mud cabins. Some workers lived in boarding houses in the new towns that sprang up along the route.15

Canal work was seasonal, which added to the transient nature of the population and shifting need for shelter. During the summer months, contractors might need as many as 1,700 workers. In winter crews could be reduced to 350.16 During the off season, some canal workers set off for work in Chicago’s pork packing houses or drifted up to the North Woods and the lumber industry. U.S. Census data from 1840 and 1850 demonstrates a transient population. Athens—Lemont’s original name— reported 1,662 inhabitants in 1840. By 1850 there were only 210 people listed as residents.17 There clearly was no incentive for the average worker to invest in housing beyond the bare necessity.18

The good pay outside observers celebrated often eluded the common workers. Many were hired for a full day’s work, while others worked three- quarter days or half-days. Some were paid by the hour. If it rained, worked stopped and no one was paid.19 Workers were not compensated during the winter months of inactivity. A chasm, therefore, existed between the lives of the well-compensated canal officials and the common laborer: The Ottawa Free Trader described this contrast:

Cold weather has now arrived and work on the canal may be considered as suspended for the balance of the season. The princely Trustees can now gather around the winter hearth and quietly enjoy their Twelve Thousand Five Hundred Dollars salary for the remaining 6 months of the year, and over their sparkling glasses devise new schemes and dupe the tax-payers of Illinois. . . . The poor and ragged workman, who had labored long and faithfully during the past season ‘from the rising of the sun to the going down of the same’ can now repair to his cheerless shanty and subsist as best he can until the return of another season.20

While many canal workers were single men, a substantial number of families accompanied their husbands and fathers to the work site— contrary to popular image of rootless vagabonds. Worker’s wives and daughters became an important part of camp life. They performed a variety of tasks in the camps, such as laundry, mending clothes, and most importantly cooking. Any extra income they earned was vital for family survival. Unattached women also could be found in I&M work camps, selling liquor in some cases, and perhaps performing more intimate services for the single men. Labor historian Peter Way has noted that these men and women became were “part of a labor force [that] became increasingly proletarianized.” This meant new expectations of work were being reshaped to meet the demands of an industrial wage system and the establishment of a regimented work pace.21

Canal work was hard, dangerous, and dirty, done with simple tools of a pick, shovel, and a wheelbarrow. On the eastern summit, laborers waded through the marshes and swamps of the Mud Lake portion of the old Chicago Portage battling mosquitos and bloodsuckers. On the Western section, they cut and blasted their way through limestone bedrock to LaSalle-Peru. Disease was a constant companion. Cholera was an episodic scourge. However, ague—a form of malaria—was the most persistent and debilitating illness for workers. The Illinois prairie often settled into muddy and marshy depressions with moist organic matter loaded with mosquitos carrying the disease. As workers disturbed this habitat, mosquitos swarmed along the canal route weakening all they stung. The connection between the bite of insects and fever was, however, lost on most medical professionals of the era. Canal foreman simply blamed the malady on heat or the vapors from decaying vegetable matter.22

Recollections in the History of Will County give evidence of the lack of understanding of the causes of the epidemic and its devastation for workers:

. . . a sickly season when 500 canal men died and were buried, and upon the graves of whom not a drop of rain had fallen from the burial of the first to that of the last. They had come from a country of a different climate, were little used to eating meat, and here they had plenty of it, and working hard in the hot sun, would sicken and die by the scores.23

Despite these hardships, Irish canal workers found few sympathizers for the challenges they faced or the conditions in which they lived. One contemporary noted that it was not surprising disease spread “among people living in such apologies for dwellings.”24 Buckingham squarely placed the blame on the Irish for their situation:

For this, here at least, poverty could not be excused, as the men were all paid at the rate of a dollar a day for their labor, had houses rent free, and provisions of every kind abundantly cheap. And yet the remedy [for filth] is within their own reach to be clean, sober and industrious is surely with in the power of every man.25

What Buckingham did not consider, however, was many men did not get that dollar a day, and soap cost twelve cents at the commissioners’ stone warehouse in Lockport—a considerable expense, even if one made that dollar a day. Wool socks sold for eighty-eight cents, and a pair of boots was two-and-a-half days’ wage. Keeping neat and clean was a considerable drain on hard-earned wages and an exercise in futility under the circumstances.26

In addition to visible squalor, American attitudes towards Irish immigrants were shaped by the Second Great Awakening—a Protestant millennial religious revival of the period. Baptists and Methodists began preaching the imminent second coming of Christ. The “saved” were called to individual self-control, social uplift, moral virtue, and temperance. The Anglo-American middle class embraced this message of personal respectability as the path to prosperity and the right to be called a gentleman. A poor, uneducated Irish immigrant exhausted by hard labor and weakened by disease, who escaped his misery through drink or vented frustration through violence, could never measure up to these expectations.27

The Irish practice of waking their dead was symbolic of the clashing values of the period. An observer along the canal work site described this practice of mourning the recently deceased:

When one ‘shuffled off the mortal coil’, the others would hold a ‘wake’; no matter how pressing work might be, everything was dropped; and if the departed had any of the world’s wealth, not a lick of work would the others do while it lasted, but drink and fight, and sometimes, in their drunken orgies, prepare the material for another wake. A grave-yard was laid out and consecrated for their special benefit, as the Catholic Church could never bury their members except in holy ground.28

There clearly was no attempt at sympathy for the poor Irish facing their own mortality on the fringes of the American frontier far from home.

Irish peasants entered the United States with pre-modern concepts of work and social obligations. They lived and labored in harsh conditions. Their environment encouraged a different concept of nineteenth century manliness in what one historian described as a “rough culture.” “Roughs,” as their contemporaries called them, defended their manliness through physical strength and prowess, excess alcohol consumption, fighting, and coarse language. They were contemptuous of discipline, rejected restraint, and felt free to indulge in violence to assert themselves. In the canal work zone, confrontations were often triggered by these conflicting values systems. Workers often chaffed at their dependent status as wage slaves. It was unmanly to be dependent. This was one factor in misperceptions and conflict between canal commissioners, managers, contractors, and Irish diggers. The canal was seen by its promoters as a harbinger of progress. Therefore, they saw work stoppages for any reason as personal moral failures and a needless obstruction to material progress.29 These conflicting value systems no doubt shaped contemporary writings, such those of Joseph Buckingham, about Irish laborers. One contractor, B.B. Snow, was full of trepidation of the Irish who he referred to as “the Devil’s own.” He countered his fear of unfamiliar and rough behavior with the threat of his own violence to keep the Irish “in line.” In 1838 he wrote his brother “I get along with the D___d Irishman. I have no trouble at all, for they all fear me.”30

Physically depleting work, disease and death, simplistic stereotypes, and clashing value systems obscure the complexity of the Irish community that came to Illinois for a chance at a new life. Not all Irish canal workers were mud-diggers. Many men who came to the I&M canal project aspired to be contractors and use the opportunity as an avenue to upward mobility. John Melody, for example, emigrated from Ireland in the early 1830s by way of New York. One of his contemporaries said he was “’a man of very frugal habits and always most industrious.” Melody saved enough money on other jobs to become a contractor on the I&M. When the canal was completed, Melody became a farmer.31

William Snowhook had an even more varied and enterprising back- ground before he came to Illinois. Born in Queens County, Ireland, he came to the United States in 1826. He worked as a printer with Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune and famed for the admonishment, “Go west young man, and grow with the country!” Snowhook worked as a levee contractor in New Orleans; a canal contractor on the Morris and Essex Canal in New Jersey, and contracted for the Maumee Canal in Ohio. He then made his way to Chicago where he partnered with William Ogden and became an I&M canal contractor. He later settled in Chicago where he succeeded in business and politics.32

Limerick-born Patrick Casey emigrated from Ireland in 1837 with three brothers and three sisters. The Casey brothers worked on canals and railways in New Jersey. Patrick left them in 1840 to start contracting on the I&M. After the canal was complete, he too moved to Chicago contracting with the city for work on streets and river dredging. Contracting for the I&M launched Owen McCarthy’s career in Chicago where his Democratic Party connections got him a job as the city treasurer and chief of police.33 Irish contractors such as these served as important mediators between the lowly Irish mud-digger and the canal engineers and commissioners, and they often played the role of community leaders in disciplining their fellow errant countrymen.

William Byrne emigrated from Ireland in 1812 and spent some time in Pittsburg until he came to work as a contractor on the I&M in 1837. He lived in LaSalle County until he died in 1873 at the age of 101 at the Sisters’ Home in Chicago. He was known as “a good mechanic, and physically and mentally superior man.”34

Michael O’Connor and his wife Sarah Land emigrated from Ireland via New York arriving in LaSalle in 1838 and immediately bought a farm. When he died in 1866 he was able to give each of his four sons eighty acres of land.35 These are just a few examples of canal workers whose lives were documented.

The canal frontier offered economic opportunities for hard-working Irishmen who were frugal and lucky enough to survive dangers from accidents or disease. However, hanging on to that hope in such miserable working and living conditions required food for the soul as well as the body. In these desperate circumstances, Irish Catholic workers found support in the universal Roman Catholic Church, whether it was from the Italian-born Bishop Joseph Rosati (1826–1843) in the French city of St. Louis or from the new See of Bardstown, Kentucky, established in 1808 which was given responsibility for the Northwest Territory.36

Catholicism in Illinois dates to the late seventeenth century French explorations of the Great Lakes and Mississippi Valley. Throughout the eighteenth century, French missionaries traversed what is now the I&M Canal Corridor as they explored and ministered to native peoples. When the British and Americans won the region in 1763 after the French and Indian War, many French Catholics and their Indian families moved to St. Louis across the Mississippi River to territory claimed by Catholic Spain. This French city became the headquarters for Catholic missionary outreach in Illinois during the canal construction period.

In 1833 Chicago’s population was estimated to be at least 150 people, one-hundred of whom were Catholics, primarily French Canadians and a few Native Americans. In April of that year, these optimistic pioneers petitioned Bishop Rosati in St. Louis for a priest to secure it as a Catholic town:

We, the Catholics of Chicago . . . lay before you the necessity there exists to have a pastor in this new and flourishing city. There are here several families of French descent, born and brought up in the Roman Catholic faith, and others quite willing to aid us in supporting a past, who ought to be sent here before other sects obtain the upper hand, which very likely they will try to do. We have heard several persons say were there a priest here they would join our religion in preference to any other.37

Father Rosati sent them a French priest, Father John Mary Irenaeus Saint Cyr, who arrived in Chicago on May 1, 1833. Father Saint Cyr offered mass in the log cabin that belonged to Mark Beaubien, who ran a lodging house, store, and a ferry at the Chicago River. For the next few years Father Saint Cyr set about raising money to buy a lot for a church. The promise of a canal, however, led to a frenzy of land speculation. Saint Cyr initially tried to buy the lot the Beaubien log cabin sat on for two- hundred dollars, but had trouble raising that sum. Within three years that property sold for $60,000. The priest then set his sights on another canal lot at Lake and State Street and was awarded the right to purchase by the canal commissioners at their valuation. However, once again the Catholic congregation could not afford the price, and the land was later sold for $10,000. In the meantime, Chicago Catholics built a modest frame building on the site. After 1837 they moved the structure to the southwest corner of Wabash Avenue and Madison Street creating the foundation for St. Mary’s Church, the oldest Catholic congregation in Chicago. By 1836, Catholic German immigrants came to Chicago so Bishop Simon Bruté sent Father Bernard Schaeffer, a German priest to assist Father St. Cyr.38

Although Rosati continued to assist the Chicago mission, in 1834 Chicago and northern Illinois was reassigned to the newly formed Diocese of Vincennes, Indiana, headed by Bishop Simon G. Bruté. Bishop Bruté began his career as a medical doctor in France, but in 1812 his interest in theology and the priesthood led him to Mount St. Mary’s College in Emmittsburg, Maryland, the headquarters of the American Catholic Church. He was consecrated a bishop in St. Louis in October 1834, and by November Bishop Bruté was settled in his new diocese that covered 53,000 miles of mostly wilderness.39 By 1835 the fifty-five year old bishop was described as a” sickly, toothless, tired old man,” but he made the difficult journey from Vincennes to Chicago to inspect his frontier outpost of his new diocese. There he was impressed with the vitality of this new Catholic community. He wrote, “Of this place the growth has been surprising, even in the West a wonder amidst its wonders. . . . Here the Catholics have a neat little church. . . . They have already their choir supported by some of the musicians of the garrison.” Bruté was warmly welcomed not only by the Catholics but also Protestants. The following year he traveled to Europe for donations and priests for his frontier diocese. He returned with nine priests and eight seminarians for his far flung diocese which came to include the canal work zone.40

When Irish workers flowed through Chicago seeking canal work, Father St. Cyr’s modest Chicago mission was stretched thin. In January 1838 he wrote to his mentor Bishop Rosati in St. Louis of the challenges in fulfilling his ministry in such a poor remote region:

Mr. Sachaeffer . . . declared to me positively yesterday evening, that in view of the circumstances, one of us two ought absolutely to go and start another parish either on the canal or someplace else, a thing impossible just now seeing that we have only a single chalice and a single missal.41

Later that year Father St. Cyr was recalled to St. Louis leaving the swelling Catholic population short of priests. Chicago Catholics complained to Bishop Rosati:

. . . we have in this town two thousand and perhaps more Catholics as there are large number of Catholic families in the adjacent country particularly on the line of the Chicago and Illinois canal, the great body of labourers on which are Catholics, to all of whom the clergy here must render spiritual assistance. The attention therefore of a clergyman speaking the English language will be indispensably necessary.42

In June 1837 Bishop Bruté sent Father James Timothy O’Meara, an Irish priest, to Chicago to assist Father Schaffer. From his base in that city, Father O’Meara made many visits to the Irish canal workers in the shanty towns of Camp Sag and Haytown near present day Lemont as well as camps located near Lockport and Joliet. In 1837 cholera from contaminated drinking water and swarms of mosquitos descended on the camps spreading malaria and overwhelming the ministry of the two Chicago priests. As a fellow countryman, Father O’Meara was very much appreciated by the Irish. Father Schaffer died of disease himself on October 2 leaving O’Meara the only priest within a hundred miles.43

O’Meara, unfortunately, took advantage of the situation and soon claimed Church property as his own which precipitated a crisis for the Church. Father St. Cyr wrote to fellow priest saying, “I was succeeded for the English speaking congregation by Father O’Meara, who proved to be a notorious scoundrel. May God preserve Chicago from such a notorious priest.”44

When another epidemic raged through the canal corridor in 1838 and further debilitated Father O’Meara, Bishop Bruté decided it was time to journey to the canal work site. He arrived in Joliet in late August where he himself tended canal workers. He also brought with him Father Julien Benoit, on loan from a parish in Indiana, and Father John Francis Plunkett to help rescue the canal corridor mission. Plunkett was a Dublin native, who left Ireland in 1834 to attend Mount St. Mary’s College in Emmetsburg. He then came to Vincennes for missionary training and was ordained in 1837 at the Cathedral of St. Francis Xavier.45 When Benoit and Plunkett arrived in the Canal Corridor, an estimated 700 people had already died during the epidemic.46 Bishop Bruté wrote to president of Mount St. Mary’s describing the harrowing work faced by the priests who witnessed nineteen canal laborers die in a matter of days.47

Bishop Bruté also had another mission which was to go to Chicago and force O’Meara to give up church property. O’Meara, however, had the Irish canal workers on his side, and told the bishop that “they would clear the church if any attempt were made to excommunicate their favorite.” Bruté then threatened to excommunicate all of them. Apparently, “this had the effect of calming them into submission, and the priest, learning this, consented to assign over all to his superiors the property of the Church which he had unlawfully withheld from it, and to leave the town on the following day. . . .”48 Unfortunately for Irish families, that was the end of Father O’Meara in the canal corridor.

The magnitude of the task of ministering to workers over such a large territory prompted Bruté to order Father Plunkett to reposition the Church’s mission headquarters along the canal from Haytown to Joliet.49 The burgeoning city was well-located on the Des Plaines River and the canal route, and in 1836 it had been selected to be the seat of Will County. By the next year it had 600 residents. It clearly was destined to become a central city of the developing territory. The mission was responsible for the territory that stretched from the south end of Chicago and from the Indiana border and westward to Ottawa. Father Plunkett served as the first resident priest in the county.50

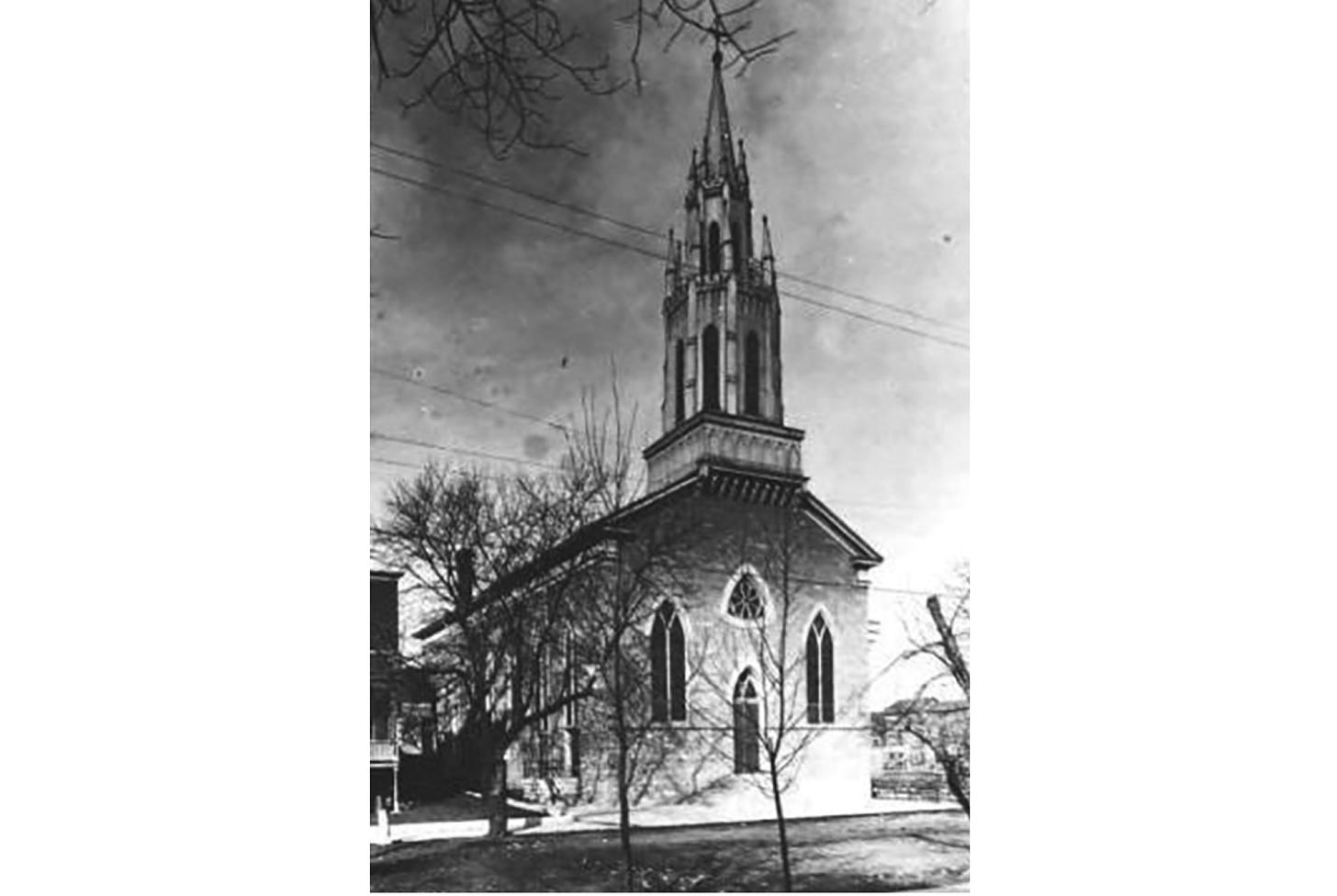

After the cholera epidemic subsided by November 1838, Bishop Bruté instructed Father Plunkett to build a permanent church in Joliet. Plunkett purchased a frame structure for $100 at Jefferson and Hickory streets. On the twenty-third of that month the priest recorded the first baptism at St. Patrick’s Church (Figure 2). By January 1839 Plunkett bought a site for a stone church on Broadway Street on a bluff overlooking the city. By the end of the year the church was ready for use.51 During that year the parish celebrated forty-four marriages. By 1840, 233 children were baptized and a school was opened and staffed by Adrian Dominican Sisters.52

Don’t Miss Part 2, Coming Next Week!

Notes

1. Joseph S. Buckingham, The Eastern and Western States, Vol. III (London: Fisher & Sons, 1842), 223–24, located in “Irish Canal Workers, 1920–1998,” Adel- man Collection, Lewis University, Chicago.

2. William V. Shannon, The American Irish: A Political and Social Portrait (New York: Macmillan, 1963), 27; Lawrence J. McCaffrey, The Irish Diaspora in America (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1976), 65; Ann Regan, “The Irish” in The Chose Minnesota: A Survey of the State’s Ethnic Groups, ed. June Drenning Holm- quist (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1981). Regan demonstrates the Irish were successful farmers in the state, but one failed colonization project served to perpetuate the myth the Irish were bad farmers (130–33).

3. Dennis Clark, Hibernia America: The Irish and Regional Cultures (New York: Greenwood Press, 1986). Catherine Teresa Tobin, “The Lowly Muscular Digger: Irish Canal Workers in Nineteenth Century America,” (Ph.D. diss., Uni- versity of Notre Dame, 1987); Ryan Dearinger, The Filth of Progress: Immigrants, Americans, and the Building of Canals and Railroads in the West (Oakland: University of California Press, 2016).

4. W.W. Stevens, Past and Present of Will County, Illinois (Chicago: The S.J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1907), 439.

5. Ibid., 326.

6. U.S. Census Records, 1850, 1870.

7. See Eileen M. McMahon, “What Parish Are You From?” The Chicago Irish Parish Community and Race Relations, 1916–1970 (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1995).

8. Carl Wittke, The Irish in America (Cleveland, OH: Case Western Reserve University, 1967), 153.

9. Later Jacob Fry and David Prickett replaced Hubbard and Archer.

10. Work Performed on Summit Division, Sections 1–22, 1838–41, Record of Payment Made to Contractors, I & M Canal Papers, Illinois State Archives, Springfield; Patrick E. McLear, “William B. Ogden: Chicago Promoter in the Speculative Era,” http://dig.lib.niu.edu/ISHS/ishs-1977nov/ishs-1977nov-283.pdf, accessed June 17, 2014; Tobin, “The Lowly Muscular Digger,” 93–95.

11. George H. Woodruff, The History of Will County, Illinois (Chicago: Wm. LeBaron, 1878), 67.

12. Tobin, “The Lowly Muscular Digger.”

13. Chicago America, 9 July 1868.

14. Buckingham, The Eastern and Western States, 223–24.

15. Charles E. Orser, Jr., “The Illinois and Michigan Canal: Historical Archaeology and the Irish Experience in America,” Éire-Ireland: A Journal of Irish Stud- ies XXVII (Winter 1992), 131.

16. John M. Lamb, “The ‘Drunken, Dirty’ Irish Build the Canal,” and “The Great Canal Scrip Fraud,” Historical Essays on the Illinois & Michigan Canal (Romeoville, IL: Lewis University, 2009), 45, 30–31.

17. Tobin, “The Lowly Muscular Digger,” 120–22.

18. Ibid., 120–22.

19. Ibid., 136.

20. Ibid., 143.

21. Peter Way, Common Labor: Workers and the Digging of North American Canals, 1780–1860 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997), 171.

22. Tobin, “The Lowly Muscular Digger,” 125–27. See also Charles Rosenberg, The Cholera Years in the U.S. in 1832, 1849 and 1866 (Chicago: University of Chi- cago Press, 1962).

23. Woodruff, History of Will County, 429.

24. Tobin, “The Lowly Muscular Digger,” 125–27. See also Rosenberg, The Cholera Years in the U.S.

25. Buckingham, The Eastern and Western States, 223–24.

26. Illinois and Michigan Canal, “Records of Supplies Furnished to Laborers,” 1846–1847, Illinois State Archives, Springfield.

27. Carol Sheriff, The Artificial River: The Erie Canal and the Paradox of Prog- ress, 1817–1862 (New York: Hill and Wang, 1996), 167; Buckingham, Eastern and Western States of America, 222–23; Michael Damien O’Carroll, “The Relationship of Religion and Ethnicity to Drinking Behavior: A Study of European Immi- grants in the U.S.” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkley, 1979).

28. Woodruff, History of Will County, 429.

29. Sheriff, Artificial River, 167; Buckingham, Eastern and Western States of America, 222–23; O’Carroll, “The Relationship of Religion and Ethnicity to Drinking Behavior.”

30. Way, Common Labor, 167; Lorien Foote, The Gentlemen and the Roughs: Violence, Honor and Manhood in the Union Army (New York: New York Univer- sity Press, 2010), 20, 33; B.B. Snow to George Snow, December 16, 1838 and 13 July 1840, George Snow Collection, 1837–1846, Chicago History Museum.

31. Tobin, “The Lowly Muscular Digger,” 98–99.

32. Ibid., 98–99.

33. Ibid., 99–100.

34. Elmer Baldwin, History of LaSalle County, Illinois: Sketch of the Pioneer

Settlers of each Town to 1840 (Chicago: Rand, McNally & Co., 1877), 380–81.

35. Ibid., 338.

36. Gilbert J. Garraghan, S.J., The Catholic Church in Chicago, 1673–1871: A Historical Sketch (Chicago: Loyola University Press, 1921), 42–43.

37. A.T. Andreas, History of Chicago: From the Earliest Period to the Present Time, Vol. 1 (Chicago: A.T. Andreas, Publisher, 1884), 289.

38. Andreas, History of Chicago, 106–7, 111, 290–91.

39. Rev. Norman G. Werling, O.Carm., The First Catholic Church in Joliet, Illinois (Chicago: The Carmelite Press, 1960), 21–22.

40. Ibid., 24–25.

41. Garraghan, S.J., Catholic Church in Chicago, 92.

42. Ibid., 96.

43. Werling, First Catholic Church, 27, 37, 39, 40.

44. Andreas, History of Chicago, 292.

45. Georgene McCanna Bankruff and JoAnn De Sandre Drake, History of St. Dennis Church, Lockport, Illinois: 150 Years of Faith, 1846–1996 (Lockport, IL: St. Dennis Church, 1996), 2; Werling, First Catholic Church, 25–27.

46. Bruté to Blanc, October 20, 1838, Bishop Simon Bruté Letters, University of Notre Dame Archives, South Bend, IN (hereafter UNDA).

47. Werling, First Catholic Church, 35.

48. Joseph Thompson, “The First Chicago Church Records,” Illinois Catholic Historical Review 4 (July 1921), 17–18.

49. Werling, First Catholic Church, 32.

50. Ibid., 13.

51. Ibid., 49–50, 54–55.

52. St. Patrick’s 150 Years: From 1838–1988, Historical Records St. Patrick Church

Pastoral Statistics 1838–1988, http://stpatsjoliet.com/documents, Accessed July 1, 2014.