Hello, everyone, and welcome to another edition of Canal Stories, a series brought to you by the Canal Corridor Association to celebrate the 175th anniversary of the Illinois & Michigan Canal and the communities that were shaped by its legacy. In 1824, a Pocket Guide for the Tourist and Traveler, Along the Line of the Canals, and the Interior Commerce of the State of New York was published to attract eastern travelers and land speculators, and to fuel the vision of US westward expansion. Soon, the opening of the Erie Canal as a “river highway," connecting New York to the Great Lakes at Buffalo, saw trade flourishing throughout the Great Lakes region.

Eastern entrepreneurs and investors championed the building of the Erie Canal, as well as an additional water highway, linking the Great Lakes at Chicago with a water route to the Mississippi River, all the way to the port of New Orleans. It came to pass in April of 1848 that this new linking water route, the Illinois & Michigan Canal, was completed and opened with great celebration at Chicago. But who were these men who placed their futures in such a seemingly small body of water? And which of them would prosper from their risks? Today, we’re exploring the life of Charles Walker, a New York man from humble beginnings who eventually grew to be one of Chicago’s most successful business tycoons. This story was brought to us by Michele Micetich, of the Carbon Hill Historical Society.

Charles Walker was born on February 2nd, 1802, in Otsego County, New York. From an early age, he distinguished himself as a quick learner, despite his limited education. As the son of a farmer, Walker spent the majority of his youth working alongside his family, only having free time to study during the three winter months of the year, when he did lessons with his teacher during the day and then with his parents at night.

By the age of fifteen, Walker had become a teacher himself, educating local children during the winter months. At eighteen, while still employed as a teacher, he turned his attention to studying law, but the sedentary lifestyle of an attorney conflicted with his active nature. At the advice of physicians, he decided it was time for a change, choosing instead to travel the countryside as a livestock buyer for his father until he was twenty-one, at which time he hired himself out to a friend as a mercantile clerk. Within two months, he had mastered the trade, opening his own business in Burlington Flats, New York. Soon enough, he was the proud owner of a grist mill, a saw mill, a potash factory, and a tannery, in addition to his mercantile.

One of Walker’s greatest strengths was his ability to view setbacks as opportunities. In the spring of 1833, he was able to turn a damaged cargo of raw hides from Buenos Aires into a profitable venture by making the leather into boots and shoes for Indian payments in Chicago. His brother, Almond, took these, along with an assortment of guns, boots, shoes, and raw leather, to Fort Dearborn in Chicago during the autumn of 1834.

It wasn’t long after this successful trading venture that Walker came to Chicago, himself, investing in a series of lots on and near the corner of Clark and South Water streets, for which he paid $15,000 in cash. Thus, Charles Walker became one of the first merchants along South Water Street, providing settlers with general merchandise, household utensils, and farm implements. But his prosperity in the Midwest did not end there.

Walker had invested in vast tracts of land as far north as Michigan and Wisconsin, as well as in Illinois, which were meant for grazing and growing. His firm purchased a few bags of grain from these surrounding midwestern farmers, which were sent by water back to his mill in New York; it is believed that this shipment of wheat was the first grain cargo ever sent from Chicago to such an eastern location.

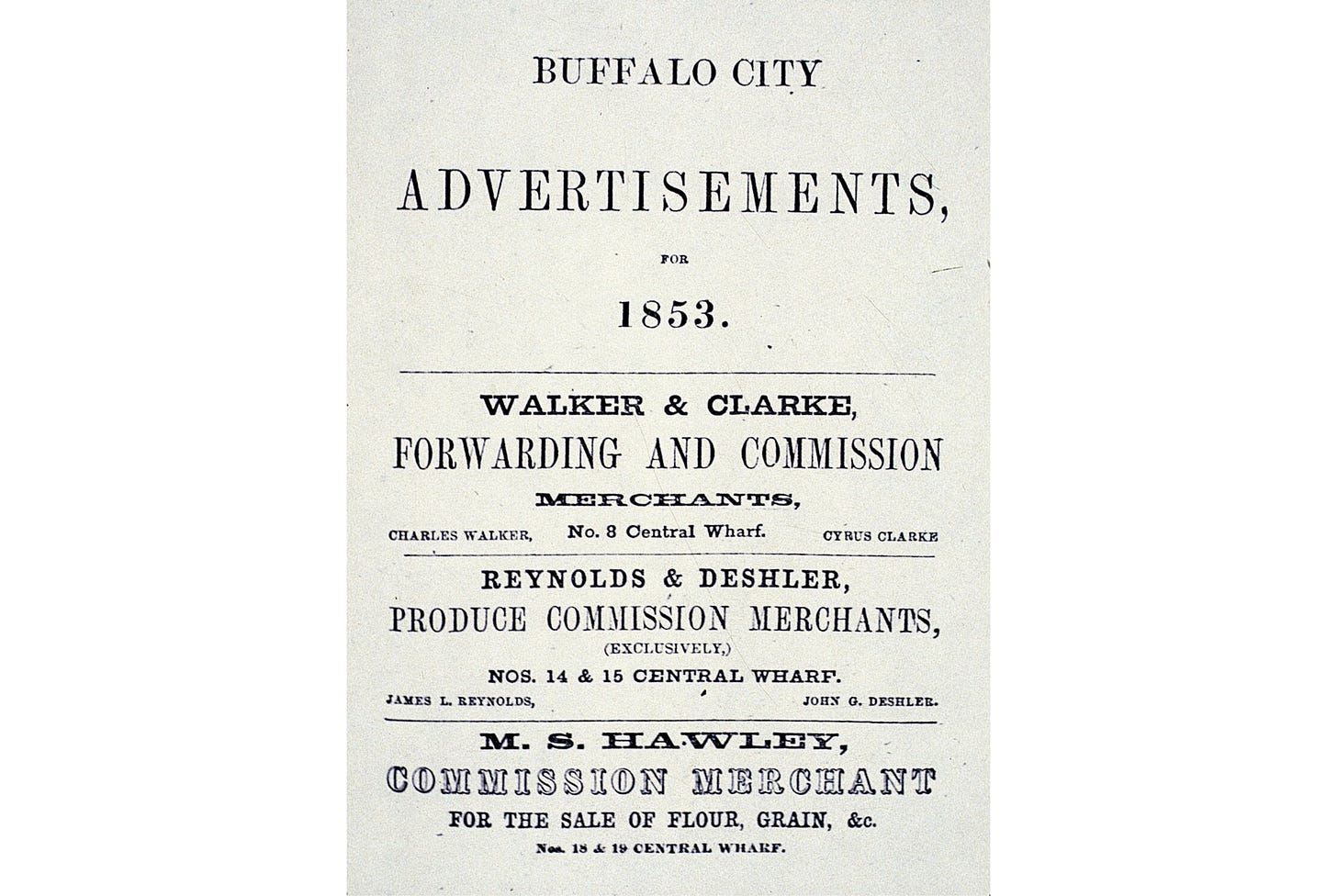

By 1851, C. Walker & Son of Chicago, Walker & Kellogg of Peoria, and Walker & Clark of Buffalo were the largest purchasers of grain from the farmers in the United States. Those few bags of grain sent eastward in 1839 were followed by a few bushels sent in 1840, and by 1851, the shipment of Walker’s grain had grown to 1,500,000 bushels.

From the early years of canal land sales, Charles Walker had bought many acres of I&M Canal land. In addition to his many joint ventures in grain mills, a large reaper factory, and acres of farm land, he used the clay found on his own farm near Morris, Illinois to partner with William White, son of prominent New York pottery man, Noah White. White’s Jugtown Pottery and Tile Works was just one of Walker’s joint enterprises and investments in Illinois, which spurred the prosperity of the I&M Canal area.

Around 1851, Walker contracted cholera, forcing him to leave the management of his affairs to his son, Charles. Though he recovered, the toll of illness led him to retire from business altogether in 1855. In 1856, he served as president and director of the Chicago, Iowa, & Nebraska line, intended to be a continuation of the Galena Railroad. Charles Walker passed away in Chicago on June 28th, 1868, leaving behind a reputation of being an innovator, a story of perseverance, and a lasting legacy as one of Chicago's early businessmen.

That concludes today’s Canal Story. Thank you so much for joining us as we continue our journey through the history of the Illinois & Michigan Canal. If you’ve enjoyed this episode, pass it along to your family and friends, leave us a like or drop us a comment, and we’ll see you again very soon.