Hello, everyone, and welcome to another edition of Canal Stories, a series brought to you by the Canal Corridor Association to celebrate the 175th anniversary of the Illinois & Michigan Canal and the communities that were shaped by its legacy. As we previously explored, the construction of the I&M Canal was a daunting task all its own, requiring a large number of workers in a variety of jobs, but just how much manpower was needed to maintain the daily operations of the canal? Today, we’re going back on the job with a look at the various occupations that made canal travel and transport possible in the 1800s.

First, let’s set the scene with a brief overview of standard canal operations. Packet boats were owned by people in Chicago and other canal towns, from Illinois river communities like Pekin, Hennepin and Peoria, to places as distant as Rochester and Buffalo, New York. The captain of a packet boat was responsible for hiring the crew and overseeing all operations of the boat that made the 22-26 hour journey between Chicago and LaSalle. Packet boat crews included a steersman, bowsman, steward, cook, cabin boy, and mule drivers. Some packet boats also carried mail, with captains serving as mailmen, sorting and delivering mail along the way. Packet boats carried up to ninety passengers, and in 1848, a ticket from Chicago to LaSalle cost $4, including meals.

The mule driver guided the team of horses or mules that pulled the packet boat on the canal. The steersman handled the tiller to keep the boat from hitting the walls of the canal or running into other boats. The bowsman used a long, iron-tipped pole to release the boat from rocks and sandbars, and to maneuver in and out of locks. The steward held his place as the concessionaire for food and drink, and the cook prepared meals for passengers.

In addition to overseeing the crew and keeping passengers happy, the captain also had to comply with numerous regulations that governed use of packet boats on the canal. This included making a list of all passengers over 12 years of age, keeping track of their names, when and where they came aboard, and where they were taken. Captains were fined $20 for not obeying this rule. If a captain presented an incorrect list of passengers, he was subject to a fine of $5 and additional fine of $10 for every passenger whose name was omitted from the list. The tolls for a packet boat were six cents per passenger and six cents for every mile the boat traveled on the canal.

HOW BIG WAS A PACKET BOAT?

The layout of a typical 75 foot-long packet boat included quarters for the crew in the bow, the kitchen in the stern, and passenger cabin in the mid-section. The passenger cabin was 50 feet in length, 9 feet wide, and 7 feet high, the approximate size of a yellow school bus.

HOW FAST DID BOATS TRAVEL?

Packet boats, pulled by horses, traveled at a brisk 5 miles per hour, while freight boats, pulled by mules and carrying up to 150 tons of cargo, moved at 1.5 to 3 miles per hour.

HOW DID TWO CANAL BOATS PASS EACH OTHER?

Because there was only one towpath along the canal, passing a boat required special maneuvering. When two boats were to pass each other, the boat heading towards Chicago had the right-of-way, but if one was a packet, then the packet had the right-of-way. To make a pass, the downstream team stepped away from the water and stopped. The downstream boat continued drifting forward causing its towrope to go slack in the water and sink to the bottom. While this was occurring, the steersman of the downstream boat guided it to the opposite bank until the upstream boat passed over the slack rope, at which point both boats could continue on their way.

WHO TRAVELED ON THE CANAL?

Between 1848 to 1852, about 26,000 people per year traveled on the I&M Canal between Chicago and LaSalle. People used the packet boats to move themselves and all of their belongings to new homes, and before the railroads, the canal was a chief route for immigrants moving further west. The boats were part of a larger transportation system in which people left Chicago via packet boat, traveled to LaSalle, then transferred to riverboats bound for St. Louis or New Orleans. Travelers from St. Louis and other southern points would take a packet boat to Chicago, and then perhaps travel via the Great Lakes to Buffalo, where they could board another packet boat on the Erie Canal to reach New York City. Businessmen in Chicago, LaSalle, and all points in between utilized the packets.

HELP WANTED: BOAT CAPTAIN

Now that we’ve established a basic overview of the canal in action, let’s take a look at our first occupation: the boat captain. Freight boat captains were responsible for all operations of a boat that carried up to 150 tons of cargo. Some captains were independent operators who owned their own boat. Some worked for others and were paid a percentage of the profits made by hauling freight. Captains hired the crew, oversaw the business of loading and unloading cargo, and ensured compliance with regulations governing the use of a boat on the canal.

Canal life on freight boats was often a family affair. The captain's wife cooked for the crew, and children as young as 6 or 7 years of age were assigned duties of their own. Young children were tethered to the deck to keep them from falling into the canal. Boys who chose to stay on the canal would often inherit their father's boats and became captains themselves.

Freight boats varied in size and design, but on average, they were 100 feet long and 17 feet wide with a hull about 6 feet high. Living quarters consisted of a 12 x 12 foot cabin at the stern (back) of the boat. A mule shed located at the boat's bow (front) housed mules, if they were kept on board, but mules were also boarded in mule barns along the canal. The middle section was the "hatch" where merchandise, foodstuff, agricultural products, or raw materials were carried.

One of the major responsibilities of the captain was to maintain accurate "bills of lading" which stated the type and weight of all freight aboard, as well as payment of tolls on these goods when they were unloaded. Captains who did not comply with this regulation were subject to a $25 fine, could have their boat detained, or their cargo confiscated.

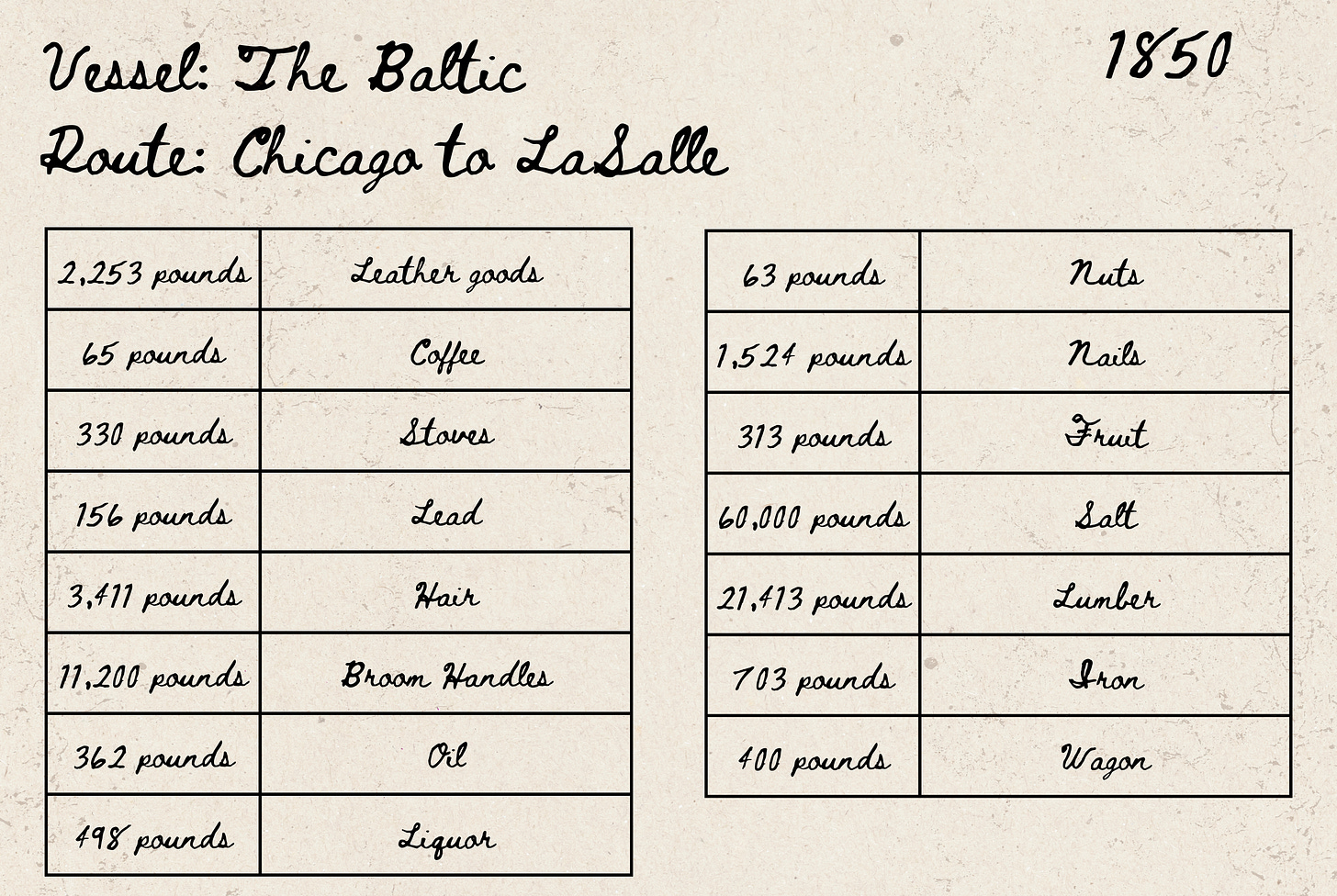

WHAT KIND OF ITEMS DID FREIGHT BOATS CARRY?

Boats going west from Chicago to LaSalle brought finished goods and merchandise from the east, as well as lumber from Wisconsin and Michigan, to help build on the prairies and plains. Boats arriving in LaSalle from the Mississippi brought resources from the south, like sugar, molasses, and fruit, along with goods from the west, like buffalo robes.

By 1870, canal boats leaving Chicago carried a much less diverse cargo, usually only 3 or 4 different items. Lumber and shingles continued to be among the more popular items transported on the canal. In 1882, over a million tons of freight was hauled on the canal.

HELP WANTED: LOCKTENDER

Next, we turn our attention to the vital position of locktender. Locktenders were on call 24 hours a day to open the locks for canal boats, often being signaled by a boat captain’s horn or shout. Although the first boat in line was to be the first boat to lock through, locktenders sometimes had to break up fights between boat captains who were arguing over who reached the lock first. Other duties included maintenance of the lock itself, repairing of leaks, and general upkeep of a stretch of canal below their lock. The canal was open for navigation when it was free of ice—usually early April through late November.

Employed by the Canal Commissioners, locktenders received $300/year and were provided a rent-free house nearby. They also had a prime opportunity for earning extra money by selling food, drink, or goods to passengers or crew on boats that waiting to lock through. Although nearly all locktenders were men, they were often assisted by their families. Research has also revealed at there were several female lock tenders in the later years of the canal's operation.

The canal had two "summit" level locks, one at Bridgeport and one near Romeoville, along with 15 locks between Lockport and the canal's terminus in LaSalle. The busiest lock along the 96-mile canal was Bridgeport's Summit, Lock #1. In 1848, the year the canal opened, 730 canal boats locked through in September. In 1851, a record of 52 boats locked through in a single day. In 1862, a total of 7,114 lockages were reported at Bridgeport, 1,000 of them in September alone.

WHAT IS A LOCK AND WHY WERE THEY NEEDED?

A canal lock is a compartment with a pair of watertight gates at each end. A series of locks functions as a "water ladder" that enables a boat to climb up or down an incline. Locks operate on the basic principal that water seeks its own level. When "locking through" a boat going downstream, the locktender began with the upstream lock gates wide open and the downstream gates closed. After the boat was maneuvered into the lock chamber, the upstream gates were closed. A small butterfly valve in the downstream gates was then opened, allowing gravity to drain the lock chamber. When the water level inside the lock chamber was the same as the level downstream from the lock, the downstream gates were opened and the boat was able to leave the lock. Raising and lowering the water level in the lock chamber took 15-20 minutes, but the entire locking process could take up to an hour.

HELP WANTED: TOLL COLLECTOR

Now we take a look at the person responsible for handling payments along the canal: the toll collector. In 1848, the Canal Commission employed two toll collectors, one stationed in Chicago and one in LaSalle. Additional collectors were added a year later in Ottawa and Lockport. Toll collectors were responsible for collecting, accounting for, and depositing tolls charged on all passengers and freight that was transported on the canal. Collectors ensured that passenger lists or bills of lading prepared by boat captains were correct. For passengers or goods unloading at his "port," the toll collector calculated and collected tolls due. Collectors had the authority to go aboard boats for inspection purposes, and to either charge fines or detain boats for inaccurate lists, incomplete bills of lading, or the refusal of the boat captain to pay tolls.

Tolls were charged per mile the boat traveled, on each passenger transported, and by type and weight of freight. Toll rates were established annually and published by the canal commission.

In 1848, passenger boats were required to pay a rate of 6 cents per mile traveled and per each passenger over eight years of age. Tolls on every 1,000 pounds of freight varied from 1 mill (one one-hundredth of a cent) on coal, 12 mills on sugar, and up to 25 mills on spirits. In 1848, salt, lumber, flour, sugar, and pork were the leading commodities carried on the canal.

When the canal was open, collectors worked from sunrise to 8 PM. Because they handled large amounts of money, they were also required to be bonded. Toll collectors received a salary of $1,000/year, and were often assisted by an Inspector of Canal Boats who was paid an annual salary between $400 and $600.

John Harris Kinzie served as the toll collector at Chicago from 1848 until 1861. Boat inspectors at Chicago included Julian Magill, Star Foot, and Samuel H. Macy.

WHAT WERE TOLLS USED FOR?

Tolls were an important source of income for the canal. Tolls helped reduce construction debt, and pay for ongoing repairs, salaries, and other operating costs. Nearly $88,000 in tolls was collected during the operating season of 1848. By 1853, a total of over $173,000 was collected at the Chicago, Lockport, Ottawa, and LaSalle toll offices.

HELP WANTED: MULE DRIVERS

Finally, we come to the wild cards of canal travel: the mule drivers. Mule drivers were responsible for guiding the team of mules or horses that pulled the boats along the 96-mile I&M Canal. They had to walk long stretches, coax stubborn mules, and occasionally rescue horses or mules that fell into the canal. Other duties included watching out for breaches in the towpath and helping to coordinate boats as they passed each other. Sleeping quarters were either on the boat where they worked or in a mule barn along the canal towpath. A boat captain generally employed two mule drivers who worked alternating six-hour shifts.

Although some were as old as 30, the majority of mule drivers were teenage boys, and they had a bit of a reputation for swearing, drinking, and stealing. The American Sunday-School Union considered work on the canal to be morally dangerous and cautioned parents to keep their sons away from this lifestyle. In their defense, mule drivers were subject to mistreatment from even more hardened boat captains and their crews, who often cheated them out of their wages. Missionaries even worked to improve conditions for these child laborers.

The most famous mule driver on the I&M was none other than James Butler Hickok, more commonly known as “Wild Bill” Hickok (1837-1876). In the first recorded fight of his long career, Bill tangled with a bully named Charles Hudson, and they both ended up tumbling into the canal. Bill mistakenly thought he had killed his opponent, and soon after, he ran off to the west, where he gained fame as a lawman and gunslinger. Aside from Hickok, the young men who drove the mules remain largely anonymous.

That concludes today’s Canal Story. Thank you so much for joining us as we continue our journey through the history of the Illinois & Michigan Canal. If you’ve enjoyed this episode, pass it along to your family and friends, leave us a like or a comment, and we’ll see you again very soon.