Hello, everyone, and welcome to another edition of Canal Stories, a series brought to you by the Canal Corridor Association to celebrate the 175th anniversary of the Illinois & Michigan Canal and the communities that were shaped by its legacy. As you explore the trails and parks of the Illinois and Michigan Canal National Heritage Area, it’s easy to see the beauty and variety of the landscape along the canal route. However, you may not realize that the distinctively shaped hills and ridges, bedrock gorges, marshes, and lakes are all evidence of the activity of glaciers and glacial meltwaters. Today, we’re exploring the Ice Age geology that shaped the face of northeastern Illinois as we know it today. This story is brought to us by the Illinois State Geological Survey, Department of Energy and Natural Resources, and was originally printed in an informational brochure by Illinois and Michigan Canal National Heritage Area.

Landforms Tell The Story

Continental glaciers invaded Illinois repeatedly during the Ice Age, a span of time from about 2.4 million years to 10,000 years ago. The modern landscape we see today records the retreat of the last major ice sheet that extended into Illinois from 25,000 to 14,000 years ago. This invasion took place during the most recent, or Wisconsin Glaciation, which geologists estimated extended from 75,000 to 10,000 years before our present time. During that time, the Laurentide Ice Sheet covered much of Canada and the northern United States. Nurtured by a continental climate much colder than our current one, the ice sheet grew as snow accumulated, and the pressure of its own weight caused it to change to ice and spread outward from its Canadian center.

The tongue of the ice sheet that flowed into Illinois came from the north. It became known as the Lake Michigan Lobe because it flowed as a river of ice through the Lake Michigan Basin before spreading out into central Illinois. When the glacier reached its southernmost limit, about 20,000 years ago, the ice was a mile thick at Chicago—an enormous weight that depressed the land beneath. Later as the ice retreated and the glacier's weight was released, the Earth's crust began to rebound. The crust is still rebounding today, especially from Milwaukee northward.

A Difference Climate

When the glaciers extended into Illinois, the climate was much different from what we experience today. At the ice margin, long-haired mastodons browsed among spruce forests. The average yearly temperatures were near or just above freezing, and most of the year's precipitation was in the form of snow. In the summer, enormous volumes of meltwater and sediment flowed away from the glacier, but during winter, river volumes were reduced to a relative trickle.

Retreat of the glaciers was caused by a gradual warming of climate in northern North America. Between 20,000 and 10,000 years ago, this climatic trend was frequently interrupted (and even reversed for short periods), which meant that the ice margin sometimes stopped melting back and at times, readvanced.

A Natural Conveyor Belt

Even as the ice sheet melted back at the front, it generally flowed outward toward its edges, picking up and carrying rocks, boulders, and soil as it moved. These materials were frozen into the bottom of the ice and dragged along at the bottom until plastic flow in the ice pushed some of them up into the moving mass. Like a conveyer belt, the glacier carried these "hitchhikers" along—some for short distances, others for hundreds of miles. Boulders and rocks transported great distances from their source are called erratics. The unsorted ice-deposited sediment of glaciers—a mixture of clay, silt, sand, and gravel—is called till. A more general term, drift, is used to refer to all the sediment derived from glaciers and their meltwaters.

Rocks frozen into the base of the glacier were the tools for gouging and polishing the land over which the ice scraped. In some places, scratches, or striations, were left on the bedrock. Many of the rocks at the base of the ice were ground up into a fine rock flour that would later become the parent material for our soils. This scraping action tended to remold the Illinois landscape, generally smoothing down the hills and filling the valleys.

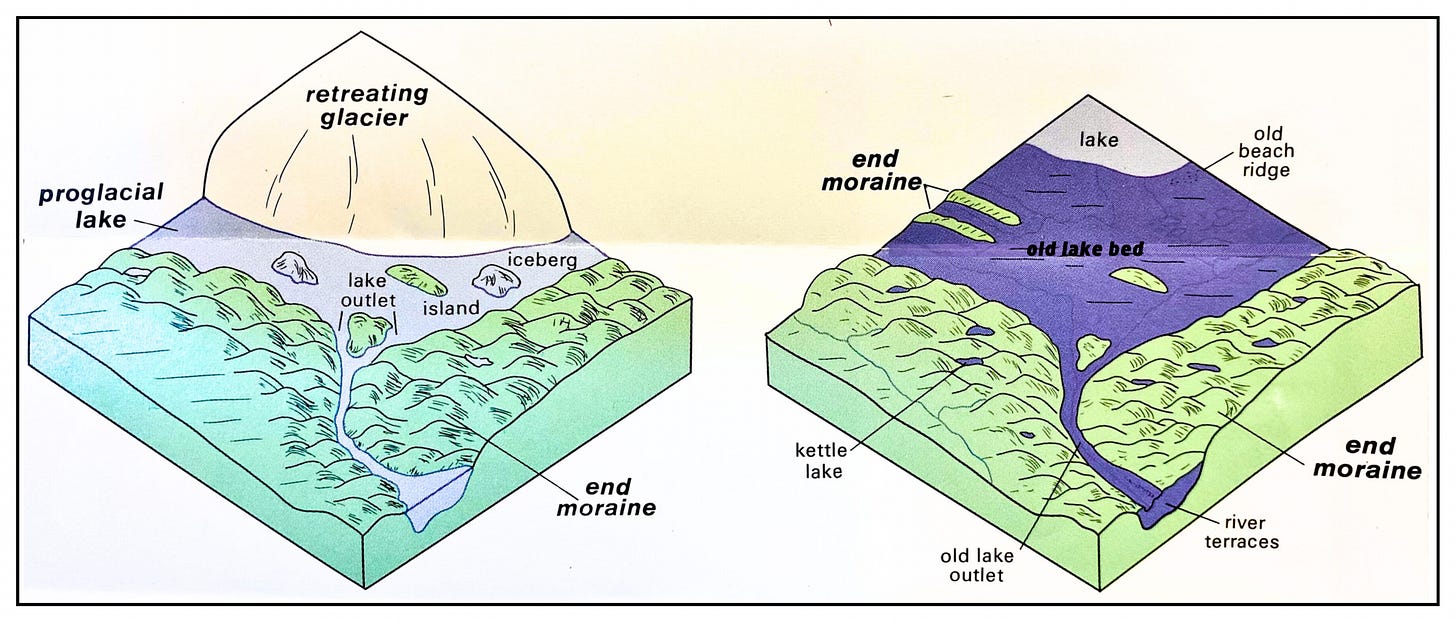

But as the ice margin melted back, new hills were formed on the Illinois landscape. These hills, called moraines, generally occurred as arcuate ridges or broad belts of irregular topography. They marked ice front positions of the retreating glacier, because even as the glacier melted back, it generally continued to flow, delivering and releasing debris at its edges. By this process, large end moraines were built in northeastern Illinois. In some places, the moraines are pocked with depressions called kettles. The kettles formed where chunks of ice broke off from the glacier and were buried in debris. Later, these chunks melted, leaving depressions in the landscape. Today, many kettles contain lakes or marshes.

Meltwater issuing from the glacier often was ponded behind older moraines, forming lakes either between moraine ridges or between the moraine and the ice front. Such lakes are called proglacial lakes. When they drained, broad, flat lake beds or plains, underlain by silt and clay, were left behind. The city of Chicago is built on one of these flat lake beds. In places, torrents of meltwater released from the glacier, or from glacial lakes, cut channels and gorges through the end moraines. In some cases, they even cut into the underlying bedrock. The channels cut by glacial meltwaters during the Ice Age are much broader than the streams that flow through them today. The valleys of the Fox, Des Plaines, and Illinois Rivers all were cut by glacial meltwater streams.

When the Wisconsin Glacier retreated into the Lake Michigan Basin, a proglacial lake known as Lake Chicago formed in front of the retreating ice margin. This lake drained by way of the Chicago Outlet, a channel through the end moraine at the southwest end of the lake. At times, other proglacial lakes also drained into Lake Chicago, increasing the volume of water in the Lake Michigan Basin, and flooding the Chicago Outlet and the Des Plaines-Illinois Valley.

Several advances and retreats of the ice margin occurred in the Lake Michigan Basin. At times, when the ice margin retreated far enough to open a lower outlet at the north end of the basin, the level of the lake in the basin fell to nearly the present level. The abandoned high beaches seen at the south end of Lake Michigan today, and the high terraces that occur along the Illinois River, provide clues to drainage history during deglaciation.

The Glacier’s Final Retreat

About 11,000 years ago, the Wisconsin Glacier retreated northward from the Lake Michigan Basin for the last time, and the level of the lake fell well below the elevation of the Chicago Outlet at the southwest end of the lake. For about 5,000 years, as the glacier retreated northward across Canada, the upper Great Lakes drained to the northeast across land that was still depressed by the weight of the ice sheet. But, as the ice sheet shrank even farther northward and the Earth's crust rebounded, the northern part of the Great Lakes Basin began to rise relative to the southern part.

About 6,000 years ago, like huge bowls being tipped to the south, the upper Great Lakes Basin once more began to spill their waters through the southern outlets at Chicago and Port Huron, Michigan. Again, the Chicago Outlet was active as the lake (now known as Lake Nipissing) drained into the Illinois River. This drainage was short-lived, however, because about 4,000 years ago, the lower outlet at Port Huron captured the drainage from the Lake Michigan Basin and the modern Great Lakes drainage system formed. After that time, no water from Lake Michigan flowed to the Illinois Valley until the Illinois and Michigan Canal was dredged in the 1800s.

Featured Landscapes

The Illinois and Michigan Canal National Heritage Area provides access to the scenic glacial landscape of northeastern Illinois. The route of the canal follows a natural low corridor between Lake Michigan on the east and the town of Peru, in LaSalle County, on the west. The low sag was cut by torrents of meltwater released during the wasting of the Wisconsin Glacier.

Four landscape units along the corridor have been chosen to reflect the Ice Age heritage of the canal route and to emphasize the variety of unique landscapes in the area:

Buffalo Rock and Starved Rock

Buffalo Rock and Starved Rock are remnants of a high terrace that was cut into bedrock in the Illinois Valley near LaSalle. The terrace surface formed as glacial meltwaters stripped away the glacial deposits and exposed the sandstone.

Later, torrents of water from glacial Lake Chicago caused further incision of the valley, creating the bedrock gorges that characterize the landscape today. The scenic canyons along the valley wall were formed as tributary streams carved into the resistant sandstone. A magnificent view of the Illinois Valley can be seen from the tops of Buffalo Rock and Starved Rock. Two of the state's most scenic state parks are located in this bedrock landscape.

Channahon Mound

Channahon Mound is a high terrace of glacial sand and gravel in the part of the Illinois-Des Plaines Valley between Joliet and Morris. The sand and gravel was deposited by glacial meltwaters released from the retreating ice margin. Later erosion by the spillwaters of Lake Chicago carved the valley even deeper, forming a lower sand and gravel terrace, and leaving Channahon Mound as a remnant of the high terrace.

Mt. Forest Island

Mt. Forest Island is a pie-shaped tract of hummocky end moraine that once stood as an island in ancient Lake Chicago. The main part of the lake was to the east, and the spillwater channels of the Chicago Outlet were to the north and south.

The hummocky knob and kettle topography found in the Palos and Sag Valley Forest Preserves indicates that this was once a landscape of ice stagnation. Today, many of the kettles contain lakes or marshes, such as Bullfrog Lake and Crawdad Slough.

Blue Island

Blue Island is a segment of an end moraine ridge that rose above ancient Lake Chicago. This former island is surrounded by beach bars and spits that formed in glacial Lake Chicago and postglacial Lake Nipissing.

Windblown sands are exposed on the western flank of Blue Island, and from the top, at the Dan Ryan Woods Forest Preserve, you can look down across the lake plain on which the city of Chicago is built.

That concludes today’s Canal Story. Thank you so much for joining us as we continue our journey through the history of the Illinois & Michigan Canal. If you’ve enjoyed this episode, pass it along to your family and friends, leave us a like or a comment, and we’ll see you again very soon.