Hello, everyone, and welcome to another edition of Canal Stories, a series brought to you by the Canal Corridor Association to celebrate the 175th anniversary of the Illinois & Michigan Canal and the communities that were shaped by its legacy. It’s no secret that Illinois has always had a complicated relationship with organized crime. Tales of crooked cops, twisted politicians, and murderous mobsters have flowed through the state since before the days of Al Capone, creating a reputation that is as feared as it is fascinating.

Contrary to what outsiders may believe, this history of laissez-faire lawbreaking and glamorized crime lords goes beyond the limits of Chicago, trickling down the Illinois River and taking hold in a small town in North Central Illinois, where a man of humble beginnings tried his luck at fortune and fame, becoming one of the most successful, and most wanted, businessmen of LaSalle County. Today, we’re going back to the golden age of gambling to explore the life and crimes of infamous casino owner Thomas Cawley. This story comes to us from our friend, Steve Stout, and was originally published in his classic book, Starved Rock Stories.

The year was 1946. Every night, the town was wild. Cars and couples packed the streets of the tiny city. Live band music filtered out past bright neon lights. Cards were dealt. Roulette wheels whirled. Throughout the county, the arms of thousands of slot machines were wrestled up and down all night long. Money was won. More money was lost.

It was dubbed “Little Reno.” It was LaSalle, Illinois.

The origins of wagering in the Illinois Valley can most likely be traced back through history to the immigrants who had carved out the Illinois & Michigan Canal during the mid-1800s. The hard-working newcomers, for whom coming to America was a great risk in itself, would gamble a portion (or all) of their earnings on most anything. To compliment these laborer bettors, coal miners and riverboat crews—the stereotypes of which were also known to enjoy gambling—also contributed heavily to LaSalle County’s gaming reputation.

This reputation continued to flourish into the next century when, in the mid-1920s, a local legend emerged. It was about this time that a stocky LaSalle Irishman, Thomas J. Cawley, the son of a coal miner, quit his low-paying street car conductor job and opened a small pool hall/cigar store with Vice Kelly, who was to die before his name became famous. The business soon became well-known for the gambling that occurred there, rather for pool or tobacco.

For the next 25 years, Cawley’s notoriety as LaSalle’s “Czar of Gambling” grew throughout the Midwest. With the expensive blessing of local politicians and police officials, he was able to keep Chicago mobsters from moving in on his territory. A belief evolved among many county residents (a belief that remained, even in the 1990s) that if vice was controlled by local men, it was a victimless activity that was acceptable to them. The affable Cawley, whose business made him wealthy and powerful, wasn’t the only local who made more than a living from gambling, but he came to be the most visible one in the community.

Around 1937, foreseeing the coming world war and the public’s need for diversions, he invested a bank-borrowed loan into his business for the expansion and remodeling of his tiny pool hall into an attractive, full-fledged casino. His vision was to make him a millionaire.

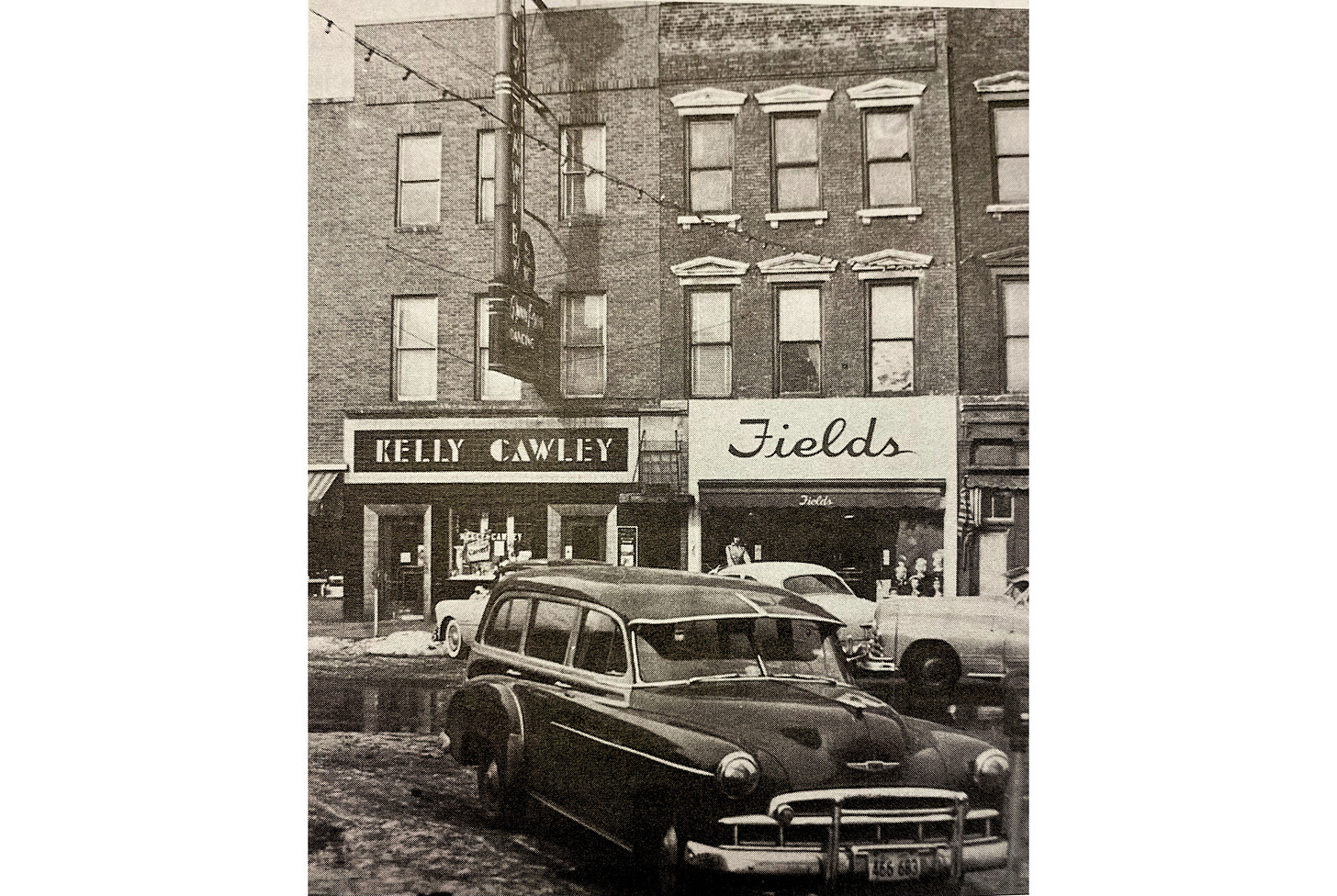

The legendary Kelly and Cawley’s building at 641 First Street was a three-story brick structure anchored in the heart of LaSalle’s downtown area. On its glazed tan exterior, a huge neon sign illuminated the block in all directions. There were three front entrances, two giving access to the first floor, with the third being a doorless stairway that led up to the second floor gaming area.

The first floor had several diversions for “pocket change” gamers (mostly local residents) centered around a long bar and dining section. The popular baseball pool and football parlay betting, each in its season, attracted thousands of dollars each week, while other activities, such as lucky bowls, punch boards, and rows of slot machines, also pulled in big money.

Instructions for all games were eagerly and politely given to any novice gamblers in the house: “Ladies and gentlemen, this game is simple. You just punch a number on the board. If you punch the lucky number, you win the prize.” The prize was usually the winner’s choice of items, such as radios, guns, etc., which were all prominently displayed along the back bar. The more expensive the punchboard game a customer wagered on, the better the choice of prizes to be won.

The first floor also reportedly served as an emergency “book” for horse racing bets. Results were regularly announced as the racing wire machine clattered away. Wagers from horse players were taken on the lower level during the few occasions when the “heat” temporarily forced the closing of the upper floors.

While small-time bettors won or lost downstairs, it was on the upper floors that the “heavy money” appeared. The small anti-gambling segments of the community charged that it was on these floors that mortgage money was lost from paychecks belonging to people who couldn’t afford to lose. However, Cawley and his cohorts said that well-to-do high rollers, pulled in from Chicago and other communities where gambling was more controlled, constituted the vast majority of the customers on the upper levels.

The country casino’s second floor was the home of an ornate round counter bar, huge roulette wheel, the ever-profitable book, 50-plus slot machines, poker rooms, and a bandstand stage for nationally-known bands and other big-name entertainers. Stars of that era, such as Donald O’Connor and George Gobel, were contacted by Cawley to perform to standing-room-only crowds. These entertainers did much to increase the nightclub’s popularity.

One of the casino’s former employees recalls, “One of Cawley’s philosophies with the gambling was to give customers the best entertainment and keep the food and drink prices low. You could order a steak dinner for something like 50 cents, or chicken for a quarter! By doing that, he attracted so many more people into the place and made enough money from the slot machines alone to more than offset all of the entertainment and food he practically gave away.”

Herbie Hummer, who was the club’s piano player and the house band leader for nearly 16 years, spoke of memories of the club before his death:

“Man those were the days…everyone was having a good time! I was first hired by ‘the old man’ (Cawley) to play piano by myself and later on, around 1939 or ’40, I put together a six-piece band for the club. We played six nights a week and the place was always busy, often to three or four o’clock in the morning. You actually had to fight the crowds on the streets and sidewalks to get from Cawley’s place to the Silver Congo Club down the way.

“The entertainment was continuous in nightclubs up and down First Street. You would see the same faces night after night. Back then, there were buses running late into the night and cabs hauling people around town. The Rock Island Rocket would bring trainloads of folks down from Chicago and you couldn’t find a motel or hotel room within miles of LaSalle. Cawley’s was a well-known place…I once saw Jack Dempsey and Dizzy Dean there!

“I often helped ‘the old man’ count money and man, I’m telling you, it was like lettuce, there was so much of it at times! I don’t remember anyone who ever said anything bad about Tom Cawley. He had a lot of friends and treated gambling as a serious business. You had to kinda admire the guy, ‘cause if someone (usually a housewife) would complain that an entire paycheck was lost in the place, he would give the family the money back without argument. The only thing that Cawley would ask was that they would never come back in to play.”

Commenting on the atmosphere of the period, Hummer, who played piano across the Illinois Valley until his death, said, “ The attitude of the local people was better back then. The town was alive! And gambling was everywhere. They even had slot machines in gas stations!”

As World War II ended and the nation’s attention returned to domestic matters, gambling houses, which had flourished for decades across Illinois and the Midwest, began to be closed down, one by one, as other priorities evolved in those communities. However, Kelly and Cawley’s (and many other clubs in the immediate area) continued to prosper and remain relatively untouched by authorities. Except for pre-warned sporadic raids, which only interrupted business for a mere few hours, there seemed to be no end in sight for popular gaming enterprises.

In the fall of 1947, a special grand jury impaneled by Circuit Court Judge Roy Wilhelm indicted four Illinois Valley mayors and three police chiefs on charges of malfeasance, due to their failure to suppress gambling. These indictments were soon thrown out by another Circuit Judge, Frank Hayes, who termed the special grand jury “a disgrace.” Judge Wilhelm called his colleague “abusive.”

The next organized attempt at clearing out the illegal operations was initiated by the LaSalle-Peru Daily News-Tribune in the fall of 1949. In front page editorials, the newspaper blasted at the conscience of the community, asserting that “legitimate business was being strangled by the flow of money to slot machines, crap tables, roulette wheels, lucky jars, horse racing, and houses of prostitution.”

The newspaper’s demands were simple. It called for honest, efficient, and competent government in LaSalle County.

To maintain focus on the problem, an investigative reporter was secretly hired by the newspaper to produce a series of articles which highlighted Tom Cawley’s bookie monopoly and “his total disregard for the law.” The results of the News-Tribune’s efforts were that several area gaming operations (not Cawley’s) were closed down for a while; however, most of the houses soon reopened as the anti-gambling articles fell off the front page. Law enforcement authorities, as well as the majority of the community itself, were just not interested in the sincere lectures from their local newspaper. The News-Tribune burned to the ground during a huge fire in December of 1949. Although the cause was rumored to be related to the anti-gambling articles, no such connection was ever officially made public.

That concludes today’s Canal Story. Thank you so much for joining us as we continue our journey through the history of the Illinois & Michigan Canal. If you’ve enjoyed this episode, pass it along to your family and friends, and be sure to tune in next week for Part II of this tale, where Tom Cawley learns that Lady Luck isn’t always on his side. We’ll see you again very soon.

Notes:

Want more great stories from Steve Stout? Check out his book, Starved Rock Stories!