Stephen H. Long

Hello, everyone, and welcome back to Canal Stories, a series brought to you by the Canal Corridor Association celebrating the Illinois and Michigan Canal and the communities that were shaped by its legacy. The Illinois and Michigan Canal had been a vision of many individuals throughout history, but who were some of the earliest canal boosters? Brought to you by Wayne Duerkes, PhD.

Marquette and Hawley were not the only advocates for a canal between Lake Michigan and the Mississippi watershed. But a few early advocates took Marquette’s suggestion to heart. Marquette felt that a canal between the south branch of the Chicago River and the headwaters of the Des Plaines River would be sufficient. This makes sense as he was considering canoe traffic only. Later, others agreed with his assessment. One such individual was Major Stephen H. Long. Stephen Harriman Long was born on December 30, 1784 in Hopkinton, New Hampshire to puritanical parents Moses and Lucy Long. Major Long’s list of accomplishments is quite vast and he is absolutely one of this country’s best topographical engineers of the Antebellum period, but the fact remains that as an army officer, he always knew to stay on task; this also fell in line with his Puritan upbringing. In 1816, Secretary of War, William H. Crawford gave Long orders to “reconnoiter little know areas in the Illinois Territory.” The task was to begin around Fort Dearborn and heading northwest looking for other advantageous places for new forts. Leaving from Fort Wayne, Indiana, Long went north to Lake Michigan and then moved westerly skirting the shoreline until he came to Ft. Dearborn.

He reviewed the harbor at Ft, Dearborn and discussed the necessary steps to make better use of the harbor by dredging out the finger of land blocking direct access to the Chicago River. He also traveled southwest to explore the Des Plaines, DuPage, and Kankakee Rivers. In this step of his exploration, in reporting back to the Secretary of War,

“A canal uniting the waters of the Illinois with those of Lake Michigan may be considered the first importance of any in this quarter of the country, and, at the same time, the construction of it would be attended with very little expense compared with the magnitude of the object.”

This standard information could have easily been read in an eastern paper from one of Jesse Hawley’s articles. Additionally, because he was a topographical engineer and he made such a claim; generalists see this as the first attempt at a canal survey. That is mythology.

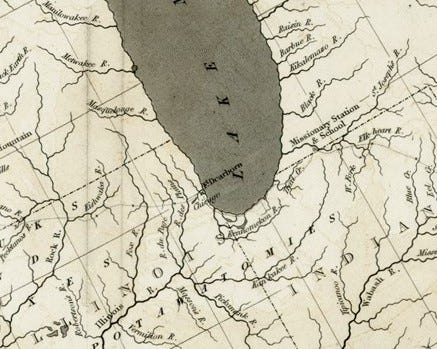

With a review of Major Long’s report, it can be easily discerned that his “plan” was merely to connect the south branch of the Chicago River to the Des Plaines River, a very short distance. The suggestion involved a little excavation, a small dam on the Des Plaines River and a lock to navigate the elevation drop. The accompanying map shows a small-dashed line between the two rivers to show the extent of his suggestion. There were no detailed measurements, surveys, or specifics, because this was not his task, it was not in his orders. Any time on this side project took him away from his general reconnoitering work, though suggesting it would be of interest to the War Department. It is fair to assess that over Major Long’s very extensive career that he provided the country with volumes of important data. But his unimproved, data-lacking suggestion of a much less minor canal does not qualify him as the first surveyor or canal planner.

The past six articles have helped set the stage for the actual building of the canal, a monumental undertaking for the young state. It is essential to know the backdrop of which this undertaking was set. The early surveys, the change to the state’s borders, the nineteenth-century marketing through periodicals and published works all coalesce to make the I&M Canal’s future possible. The collection of documents kept the canal in the eyes of the people and the government, and as we all know, out of sight, out of mind. The next series of articles will discuss the formalization of the canal’s construction crew and broader design. After that, we will head into the construction phase. At this point it is extremely important to realize that the actual development and construction phases were as important to early Illinois, if not more, than the actual opening and usage of the finished canal. Because the proposed canal gave the vast number of migrants heading west the one thing that they were all looking for: hope.

That concludes today’s Canal Story. Thank you so much for joining us as we continue our journey through the history of the Illinois & Michigan Canal. If you have enjoyed this episode, pass it along to your family and friends, be sure to leave us a like or drop us a comment, and we will see you again very soon.