The National Significance of the I&M Canal

A Look at the I&M Canal's Impact as the Final Link in an 1840s Water Highway

Hello, everyone, and welcome to another edition of Canal Stories, a series brought to you by the Canal Corridor Association to celebrate the 175th anniversary of the Illinois & Michigan Canal and the communities that were shaped by its legacy. Today, we will be exploring the National Significance of the I&M Canal, as written by Ronald Scott Vasile. He worked as a public historian for the Canal Corridor Association for eight years, is a teacher of AP US history and anthropology at Lockport Township High School in Lockport, Illinois, and worked as a collections manager and archivist at the Chicago Academy of Sciences.

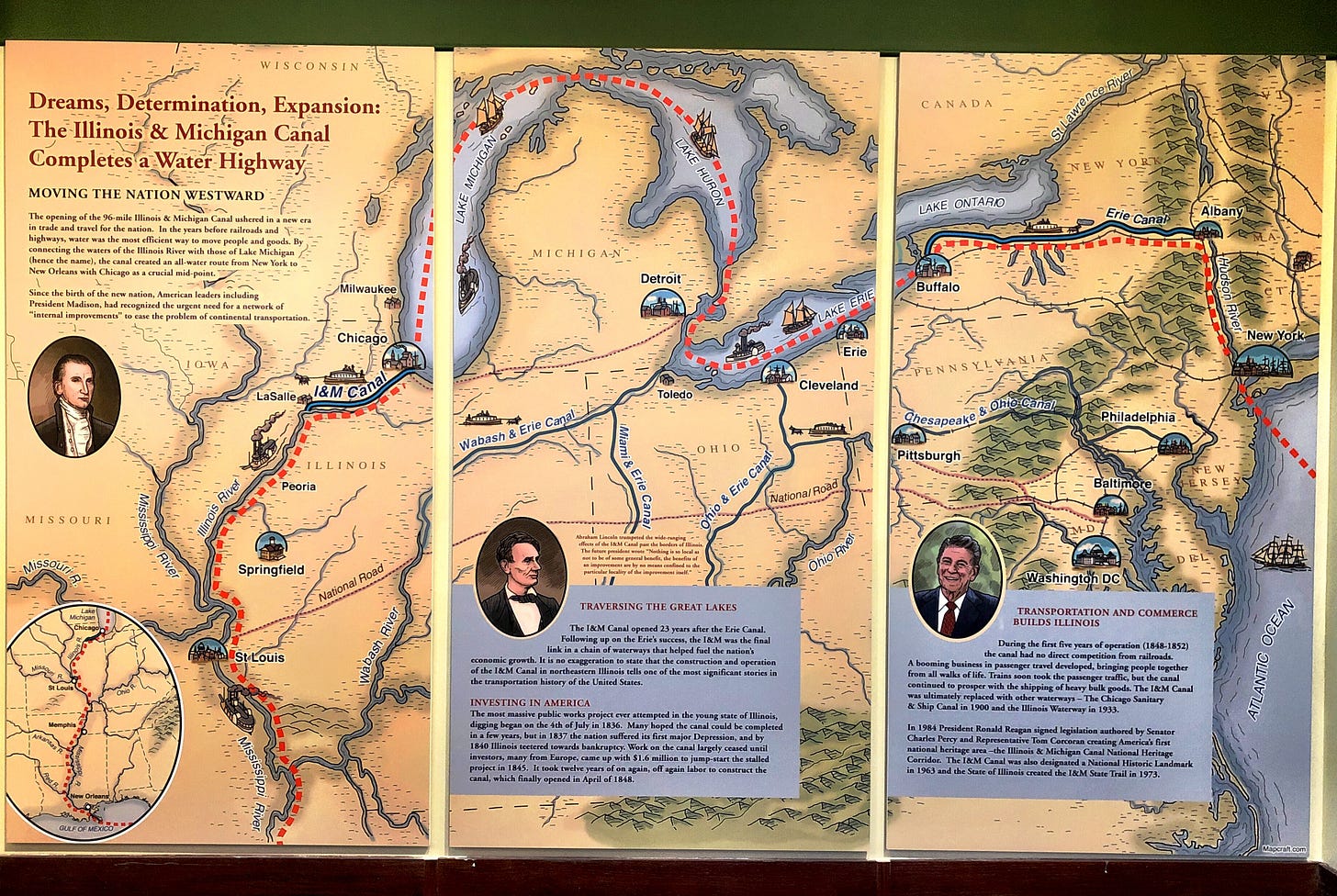

The l&M Canal was the final link in a national plan to connect different regions of the vast North American continent via waterways. Linking the waters of the Illinois River (and ultimately the Mississippi River) with those of Lake Michigan, the idea of the canal went back to Louis Jolliet and the early French fur traders of the 1670s.

Since the birth of the new nation, American leaders had recognized the urgent need for a network of "internal improvements" to ease the problem of continental transportation. The success of the Erie Canal, completed in 1825, marked a period of intensive canal building in the U.S. Indeed, the years from 1790-1850 have been characterized as the Canal Era. This chapter in our nation's history has been largely overlooked, as most historians have focused on the railroads as the prime force behind America's development.

The l&M Canal is nationally significant for many reasons. In 1827, the Federal Government gave the State of Illinois nearly 300,000 acres of prime farmland, the sale of which would finance construction of a canal. The l&M Canal shares with the Wabash Canal in neighboring Indiana the distinction of being the first American Canals to receive a federal land grant toward its financing. This precedent is of great historical interest, as it later served as the model for the first federal land grant to support a railroad – the Illinois Central Railroad.

In 1843, with construction of the l&M Canal stalled due to the State of Illinois's near bankruptcy, investors from New York, England, and France put up $1.6 million to complete the canal.

On its completion in 1848, the l&M Canal created a new transportation corridor. Travelers from the eastern U.S. took the Erie Canal to Buffalo, New York, where steamboats brought them through the Great Lakes to Chicago. Transferring to canal boats, a 96-mile trip on the l&M Canal brought them to LaSalle/Peru. Here people boarded river steamers bound for St. Louis and New Orleans. During the years of the California Gold Rush, many emigrants traveled part of the journey on the l&M Canal. During the nation-wide cholera epidemic of 1849, the disease came to Chicago via passengers on the l&M Canal.

Abraham Lincoln trumpeted the effects of the l&M Canal. While acknowledging that the l&M Canal was entirely within the confines of one state, (Illinois) he noted that its benefits extended far beyond those borders, reducing the cost of transporting goods, thus benefiting both buyers and sellers. "Nothing is so local as not to be of some general benefit,” wrote the future President. "The benefits of an improvement are by no means confined to the particular locality of the improvement itself."

While the canal enjoyed only five years free of railroad competition, these years were absolutely critical in launching Chicago on its path to urban greatness, and in spawning a dozen other towns along its banks that would soon industrialize and help consolidate the western end of the American Manufacturing Belt in northern Illinois. The opening of the Illinois & Michigan Canal radically reduced the costs of transferring goods, particularly grain, lumber, and merchandise, between Midwestern prairies and the East via the Great Lakes trading system. For the first time, the canal allowed goods from the southern U. S., including sugar. salt, molasses, tobacco, and oranges, to be shipped to Chicago. By cutting travel times, the l&M Canal also precipitated a new era of travel for people from the south to the north, and vice versa.

That concludes today’s Canal Story. Thank you so much for joining us as we continue our journey through the history of the Illinois & Michigan Canal. If you’ve enjoyed this episode, pass it along to your family and friends, and we’ll see you again very soon.